A Futurist Can't Win

Kevin Kelly | Paul Krugman on Progressivity | From the Archives | Deep Acting

Quote of the Moment

This is the futurist’s dilemma: Any believable prediction will be wrong. Any correct prediction will be unbelievable. Either way, a futurist can’t win. He is either dismissed or wrong.

| Kevin Kelly, The Futurist’s Dilemma

The story of my life.

Progressivity

Paul Krugman picked up on a theme posed by Ezra Klein, where the question is (once again) ‘where’s the productivity gone to?’, in this case regarding the construction industry. I was happy to hear Krugman make what I think of as the Progressivity argument:

[Klein’s] discussion had me thinking about a debate in economics that I’m old enough to remember taking place in real time: the attempt to explain the drastic economywide slowdown in productivity growth in the 1970s. This debate had a lot in common with the current discussion of construction productivity. And it also raises some questions about whether productivity is the right measure of economic success.

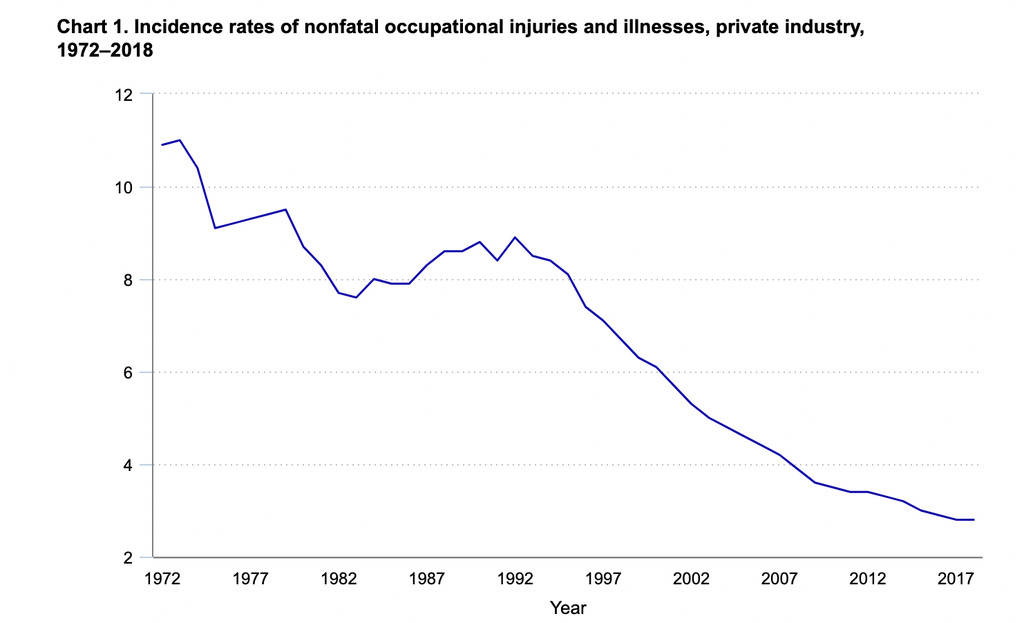

Krugman notes that construction was quite dangerous in the 1970s when productivity was higher in that sector.

It turns out that American workplaces in the early 1970s were very dangerous places by modern standards. And I don’t know about you, but a greatly reduced probability of getting injured or sick on the job seems like progress to me.

It is not, however, progress that shows up in measures of real gross domestic product, and hence in productivity data. So productivity numbers show only the costs, not the benefits, of safety regulations.

So, productivity, as currently pursued and measured, externalizes costs like safety (and pollution, childcare, and a long list of other issues). He goes on:

So part of the productivity slowdown during the 1970s probably represented not so much a loss of dynamism as a shift in priorities — deliberate choices to make workplaces safer and skies cleaner, even at the expense of production.

Were these choices defensible? Definitely yes. Could the policies have been better applied? Of course — but when isn’t that true?

Now, I am quite willing to believe that the trade-offs on construction have been much worse than average, without equivalent social benefits to those 1970s policy choices. The problems with NIMBYism are huge and obvious, and they’re presumably part of a larger picture in which too many interest groups have the power to make construction difficult, even when those projects would be very much in the public interest. Nonetheless, it’s important to realize that making it easier for businesses to do what they want isn’t always a good thing.

That’s a line to save: making it easier for businesses to do what they want isn’t always a good thing.

From the Archives

5 dumb hiring trends (2019) | Anisa Purbasari Horton pulls five useless categories of interview methods, like unstructured interviews, which introduce all sorts of bias into hiring.

…

What Really Helps Employees to Improve (It’s not Criticism) | Knowledge@Wharton wrote about Marcus Buckingham's 2019 keynote at the Wharton People Analytics Conference, where he called most of the premises of HR 'lies'.

Deep Acting

A few years ago, I came across the term ‘deep acting’ in an essay by Kathi Weeks, where she extrapolates from ‘traditional forms of women’s work’ to the general nature of work for all:

One of the remarkable features of the contemporary post-Fordist economy is how traditional forms of women’s work have come to characterize so many different kinds of employment. As many feminist political economists have by now recognized, "the conditions elaborated by feminists to surround women’s labour have now become generalized conditions of work" (Adkins and Jokinen 2008, 142). Consider, for example, how the modes of mental and manual labor once disaggregated across many industrial jobs are now often integrated, together with labors of the heart and soul, in postindustrial production. To the extent that the flexible, caring, emotional, cooperative, and communicative model of femininity has come to represent the ideal worker, women’s work under Fordism has arguably become the template for, rather than merely ancillary to, post-Fordist capitalist economies.

One consequence of these developments is that more and more of workers’ subjectivities become folded into and fused with their identity as workers. To configure work as the center of our identity requires a reconfiguration of the self in its relationship to work. This is facilitated by the fact that, mimicking the unbounded qualities of household care work, in the contemporary economy the borders that were once thought to separate waged work from nonwork time, spaces, practices, and relations are widely acknowledged to have broken down. Waged work and its values have thus come to dominate ever more of our time and energy.

She goes on to focus on the modern theme of love and romance in our relationship to work:

Popular management and career consultants tell us that love and happiness at work are good for both employers and employees, and the only thing the employee needs in order to accomplish this affective rewiring and emotional disciplining — and employees, they endlessly repeat, are the only ones who can do it — is “wide-eyed enthusiasm” (Kjerulf 2014, 172). Do what you love, they preach; learn how to love your work in ten easy steps. Fall back in love with your job. Learn even to love the work you hate. The future of work is happy. An often-cited quotation from one of the inspirational figures of this trend, Steve Jobs, distills many of the key themes of this literature:

‘Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking. Don’t settle. As with all matters of the heart, you’ll know when you find it. And, like any great relationship, it just gets better and better as the years roll on. So keep looking until you find it. Don’t settle.’ (2005)

This has become a central tenet of contemporary business culture. Despite neoliberal commodification of workers — look at the massive layoffs across the tech sector, which only a year ago would have claimed ‘our greatest asset is our employees’ now jettisons them in a heartbeat — they had been preaching the Jobsian ideal of being in love with your job, perhaps more so than with your family. [Emphasis mine.]

The ideology of romantic love born of the separate spheres, an idealized and feminized model of love, is being harnessed, not only to continue to assign domestic work to women, but to recruit all waged workers into a more intimate relationship with waged work.

Just as the Protestant work ethic can be construed as an ideology propagated by the bourgeoisie and inculcated into the working classes, the current discourse of love and happiness at work undoubtedly finds its greatest resonance within the professional and managerial classes. But just as the work ethic in the U.S. today circulates widely in the culture — as well as among employers, public officials, and policymakers — as an unquestioned value, the mandate to love our work and be happy with it is arguably becoming increasingly hegemonic as a cultural script and normative ideal. The improbability of its claims about how workers can find meaningful delight in their jobs, its seeming irrelevance to the real conditions of most employment, has not prevented the ideals of love and happiness in and through work from coming to set a broader cultural standard, one that affects a growing swathe of workers. To be competitive in this job market and to hold on to, let alone advance within, whatever job we might manage to land, we will need to adapt, in some way and to some degree, to the workplace-feeling rules and affective expectations that are increasingly being imposed up and down the labor hierarchy. Whether that means an employee will be required to employ the transformative effects of deep acting to satisfy an employer’s expectation of happy workers, or only to display the approved countenance by means of surface acting, depends on the employee’s location in the waged labor force.1 But given the shift in the balance of power between labor and capital under neoliberal restructuring, which bestows on employers the luxury of “playing the field,” more and more prospective employees mindful of their ongoing employability will need to work continually on their lovingness and aptitude for happiness at work.

Weeks’ essay continues, and I recommend that anyone interested in the overlap between ‘work love’ and self-identity to read it in its entirety.

I recently read a research paper by Alison Gabriel and colleagues that suggests deep acting is common in the workplace because it betters relationships with others:

We first asked our study participants to rate the extent to which they regulated their emotions with coworkers using two emotion regulation strategies — *surface acting* and *deep acting*. We also asked them about the benefits of engaging in these strategies towards their coworkers.

When you feel one emotion and attempt to express another, you’re surface acting. Imagine you arrive at work frustrated after a bad commute. You might fake a smile to a coworker while you’re grabbing a morning cup of coffee, even though you’re still not feeling particularly positive inside.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Work Futures to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.