Meaningful Work For All

Elizabeth Anderson | What Sort of Future Do We Want? | Australian 'Right to Disconnect' | Factoids

Quote of the Moment

One place to build democracy is in the workplace. Neoliberal workplace governance under shareholder capitalism has de-skilled work and degraded workers. It has also inflicted vast moral injury on workers by forcing them to participate in harming other people, animals, and the environment in the course of maximizing profits. If workers had a powerful voice in the government of their workplace, they would not choose to reduce themselves to de-skilled drudges or inflict moral injury on themselves. Democratizing work is a powerful way to promote democratic skills and dispositions, demonstrate that democracy can respond to ordinary people’s concerns, and thereby strengthen democracy at the state level. Most people want meaningful work as understood in the progressive work ethic tradition: work that affords a means for a person to exercise their agency and skill in the course of helping other people. Democratizing work, through workers’ cooperatives and enhanced models of codetermination, is a promising way to secure meaningful work for all.

| Elizabeth Anderson, The Struggle for Meaningful Work [emphasis mine]

Anderson expands on the themes of this essay in her most recent book, Hijacked, which I will be reviewing as soon as possible.

Anderson is also the author of Private Government: How Employers Rule Our Lives (and Why We Don't Talk about It).

What Sort of Future Do We Want?

I spent some serious time in the past weeks considering how I might go about one of my planned projects for the year: the Work Futures 2024 Report. I was winnowing through various work-related topics, and considering how to represent them in a graphical and conceptual way.

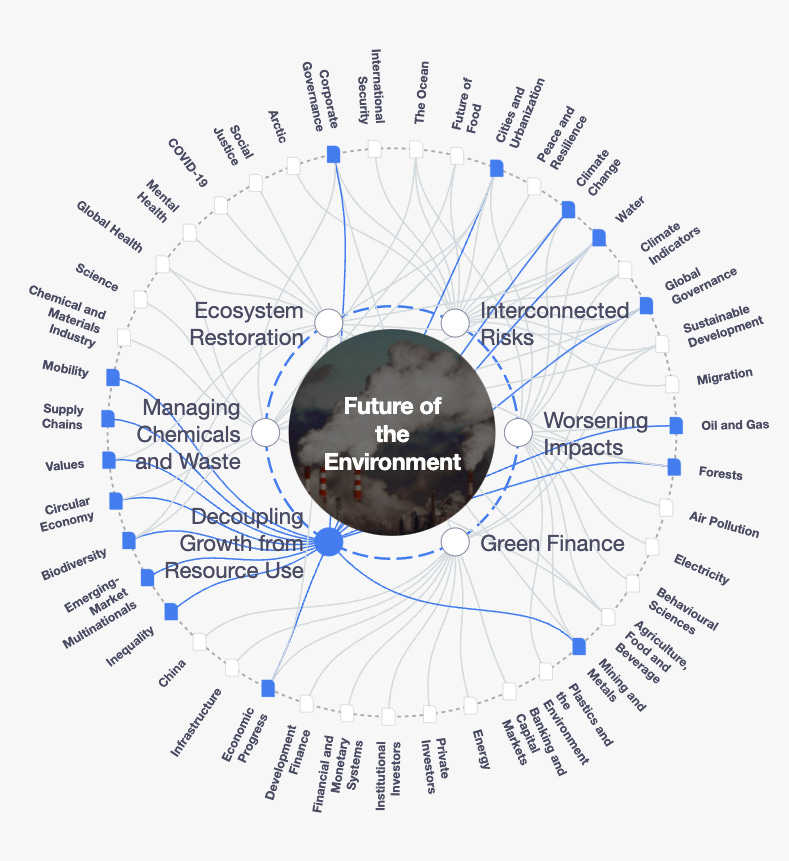

I looked at charts like this, cribbed from a World Economic Forum report on the Future of the Environment.

On one hand, such a model — one with dozens of topics acting as terminal nodes in a network of challenges, threats, or motivating forces, likewise connected in a network — might seem appealing. However, after grappling with it for a time, it seemed too top-down, and with too many built-in preconceptions.

Likewise, the chart above — and the thinking behind it — seems to miss the obvious: everything is related to everything else. The ‘Air Pollution’ node in the chart above has a serious impact on ‘Global Health’, but that linkage isn’t shown, explicitly. Yes, the chart shows one selected theme — ‘Decoupling Growth from Resource Use’ — and links outward to the terminal nodes, like ‘Inequality’. But why isn’t ‘Agriculture, Food and Beverage’ linked to that theme as well?

In the final analysis, such a chart would have to arise after some analysis was applied to each of the terminal nodes, and then the themes could arise. So, the chart was likely the result of a bottom-up model.

In my case, then, what I need is to define a list of topics — the terminal nodes of a Future of Work model — and write at least a first-order take on each, such as ‘The New Luddites’ or ‘Democratizing Work’.

And wouldn’t a report on the future of work be based on some sort of timeline? Note that the time dimension seems completely absent in the WEF chart, above.

I experimented with a timeline model and realized something critically important: you can’t conceptualize future events without having an opinion. Why should some hypothetical series of events occur? How would a shift in people’s thinking manifest itself in 5 or 20 years time? What sort of outcome do I think would be best for all involved, and who would make that state a reality?

I realized that I would have to be opinionated. I would have to take a stand, and a stand of the sort that Elizabeth Anderson has staked out in the Quote of the Moment, above.

Here’s the timeline that crystalized this thinking for me:

I came to see that behind the swirling possibilities of the Future of Work is a growing contention between what Anderson calls the progressive, democratic (dare I say socialist?) work ethic and the conservative, neoliberal, (let’s just say it: capitalist) work ethic. This contention is shown in the ‘New Luddites’ timeline above.

This insight led me to reread Anderson’s essay, and a dozen or so more.

I also realized that Anderson’s piece had the wrong title. She is not laying out an argument for making work more 'meaningful', but a call for casting off the chains of subservience baked into the contemporary work culture due to the dominant conservative work ethic.

Therefore, the Work Futures 2024 Report will be dedicated to advocacy for a societal transformation toward a more progressive ethos of work — and the institutions that shape work — based on what may best be considered socialist humanism. Part of that advocacy is strident opposition to the central premises of the conservative work ethos, such as the primacy of unregulated markets, the financialization of business, and the commodification of work.

I am reminded of the contour of humanism laid out by Claude Levi-Strauss:

A well-ordered humanism does not begin with itself, but puts things back in their place. It puts the world before life, life before man, and the respect of others before love of self.

And it puts the good of the people before anti-human, exploitative economics.

I will be dribbling out sections of the Report week by week, some parts for paid subscribers and most for all readers, here. As I write the scenarios for the subsections, I expect to see the emergence of the overarching themes, as well.

Australian ‘Right to Disconnect’

Australians will soon be able to turn off when they are off the clock. A new law has passed the Oz Senate, and is highly likely to pass in the House as well. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said,

Someone who is not being paid 24 hours a day shouldn’t be penalized if they’re not online and available 24 hours a day.

Natasha Frost and Isabella Kwai wrote,

Australia follows in the footsteps of European nations such as France, which in 2017 introduced the right of workers to disconnect from employers while off duty, a move later emulated by Germany, Italy and Belgium. The European Parliament has also called for a law across the European Union that would alleviate the pressure on workers to answer communications off the clock.

[…]

Unions and other industrial groups have long argued that employees have the right to disconnect, but the issue gained salience during the pandemic, when a widespread shift to remote work led to the further blurring of boundaries between home life and work life.

Then, the defenders of the conservative work ethos attack the proposal:

Critics of the new rule, among them businesses groups and opposition lawmakers, have called it rushed and an overreach from the government, expressing concerns that it could make it harder for businesses to get their work done.

“This legislation will create significant costs for businesses and result in less jobs and less opportunities,” Bran Black, the chief executive of the Business Council of Australia, said in a statement.

“None of the measures are designed to improve productivity, jobs, growth and investment, which are the ingredients of a successful economy,” said Michaelia Cash, a senator from the right-wing opposition Liberal Party.

Oh yes, they’d be much happier if the government would leave it to business owners to self-manage, with the threat that people will lose their jobs.

Factoids

A report on D&I in the film industry found that a total of 116 directors were attached to the 100 top-grossing US domestic films in 2023, but just 14 of them – or 12.1% – were women. Only four of them (3.4%) were women of color. | Dense Discovery

…

Talk about optimizing the wrong things.

…

Russia has lost 87 percent of its preinvasion active-duty ground troops and two-thirds of its tanks that it had prior to its invasion of Ukraine. | Thomas Friedman

…

China's population fell for a second consecutive year in 2023, as a record low birth rate and a wave of COVID-19 deaths when strict lockdowns ended accelerated a downturn that will have profound long-term effects on the economy's growth potential. The National Bureau of Statistics said the total number of people in China dropped by 2.08 million, or 0.15%, to 1.409 billion in 2023. That was well above the population decline of 850,000 in 2022, which had been the first since 1961 during the Great Famine of the Mao Zedong era. | Reuters