Innovation Engine

The new imperative for managing innovation: consider seemingly unreasonable ideas, suspend early judgment, and defy dogma.

Quote of the Moment

If you know it’s going to work, then it’s not innovation.

| Tomas Chamorro-Premusic

A Wider Net

My recent experience in the Substack Grow workshops has led me to reconsider earlier choices about Work Futures; hopefully, for the better.

I had several comments from readers in the discussion about the recasting of the tagline for the publication (which is now ‘the past, present, and future of work, and its impact on society and our lives’)1 who pointed out that my interests are somewhat larger than ‘the future of work’. As one result of that, I will be occasionally juxtaposing stray bits to the form and function of Work Futures, which I am calling ‘A Wider Net’, which sources from areas adjacent to the conventional discussions of work policy, theory, or practices. In today’s example, below, some behavioral economics.

Behavioral Economics: Much Anew About Nudging

Some McKinsey analysts interviewed economists Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler about the impact of their work on ‘nudging’:

McKinsey: For the uninitiated, what is nudging?

Cass Sunstein: A nudge is an intervention that maintains freedom of choice but steers people in a particular direction. A tax isn’t a nudge. A subsidy isn’t a nudge. A mandate isn’t a nudge. And a ban isn’t a nudge. A warning is a nudge: “If you swim at this beach, the current is high, and it might be dangerous.” You’re being nudged not to swim, but you can. When you’re given information about the number of fat calories in a cheeseburger, that is a nudge. If a utility company sends something two days before a bill is due, saying that “You should pay now, or you are going to incur a late fee,” that is a nudge. You can say no, but it’s probably not in your best interest to do so. Nudges help people deal with a fact about the human brain—which is that we have limited attention. The number of things that we can devote attention to in a day or an hour or a year is lower than the number of things we should devote attention to. A nudge can get us to pay attention.

[…]

McKinsey: Nudging is tied very closely to the concept of “choice architecture.” What is that? Can you remind us?

Cass Sunstein: Really, any situation where you’re making a choice has an architecture to it.[1] The owner of a website may put certain things in a very large font—the things that the private or public institution really wants you to attend to and maybe choose—and keep certain things hidden in small print at the bottom. And it turns out that small differences in this kind of architecture can lead to large differences in social outcomes. If you have a choice architecture where people must opt in, for instance, the participation rate is a lot lower than if the architecture prompts them to opt out.

The researchers treat the bureaucracy of choice architecture — the friction in systems and institutions that impose a tax on trying to move ahead — as ‘sludge’:

McKinsey: The increased use of technology and smart disclosures seem important for reducing sludge in decision making. That’s one of the new concepts you introduce in this edition of the book. What is sludge?

Cass Sunstein: Think of it as frictions or burdens or barriers that make it hard for you to get where you want to go. It’s the company that keeps you waiting on the phone for hours to resolve an issue with a product. Or if you’re trying to get a permit to build something or to do some kind of job that you’re qualified for, you may have to fill out a 40-page form, go in for an interview, deal with six people who are hard to get ahold of—that’s sludge. By the latest counts, the US government imposes 11 billion annual hours of paperwork on people. Some of it is justified; you can have cases where people are rightly asked to prove something, and that takes some administrative burdens to navigate. But often, the level of sludge that people are asked to endure is much too high. It’s like a wall between people and something that can make their lives much better.

[…]

McKinsey: If I’m an executive, how should I think about reducing sludge and designing and deploying nudges in my organization?

Cass Sunstein: Dick and I have both learned that the best way for organizations to reduce sludge and develop a capability in nudging is to bring in people who have some training in this area. It may be that they studied behavioral economics at university, or they have experience in the field with nudging.

It’s no secret that social media companies have behavioral expertise which, in some cases, they’re using for good. Some companies that sell food and drink are thinking hard about how to use nudges to increase profits and, simultaneously, do better by their customers.

The second-best thing, however, which can help a lot, is to train people in-house on the basics of behavioral science or behavioral economics. It’s not that technically complicated. And if you have people who are willing, who have fun with it, and who are eager—maybe they are doing this as half of their job—they can make a massive difference within a company.

Work Won’t Love You Back: Vocational Awe

Anne Libbey uses the term ‘minimum viable passion’ in Minimum Viable Passion: On Management #37, but never defines it, alas.

But Libby turned me on to Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies We Tell Ourselves by Fobazi Ettarrh, someone totally new to me.

Vocational awe describes the set of ideas, values, and assumptions librarians have about themselves and the profession that result in notions that libraries as institutions are inherently good, sacred notions, and therefore beyond critique. I argue that the concept of vocational awe directly correlates to problems within librarianship like burnout and low salary. This article aims to describe the phenomenon and its effects on library philosophies and practices so that they may be recognized and deconstructed.

I think the concept of vocational awe can be generalized to any institution or occupation, not just libraries, where individual identification with the industry, practice, or imagined importance of the work can lead to exploitation of those emotionally tied up in the halo around the work.

It is important not to forget awe, which represents the effect. Merriam-Webster defines awe as “an emotion variously combining dread, veneration, and wonder that is inspired by authority or by the sacred.”

[...]

The problem with vocational awe is the efficacy of one’s work is directly tied to their amount of passion (or lack thereof), rather than fulfillment of core job duties.

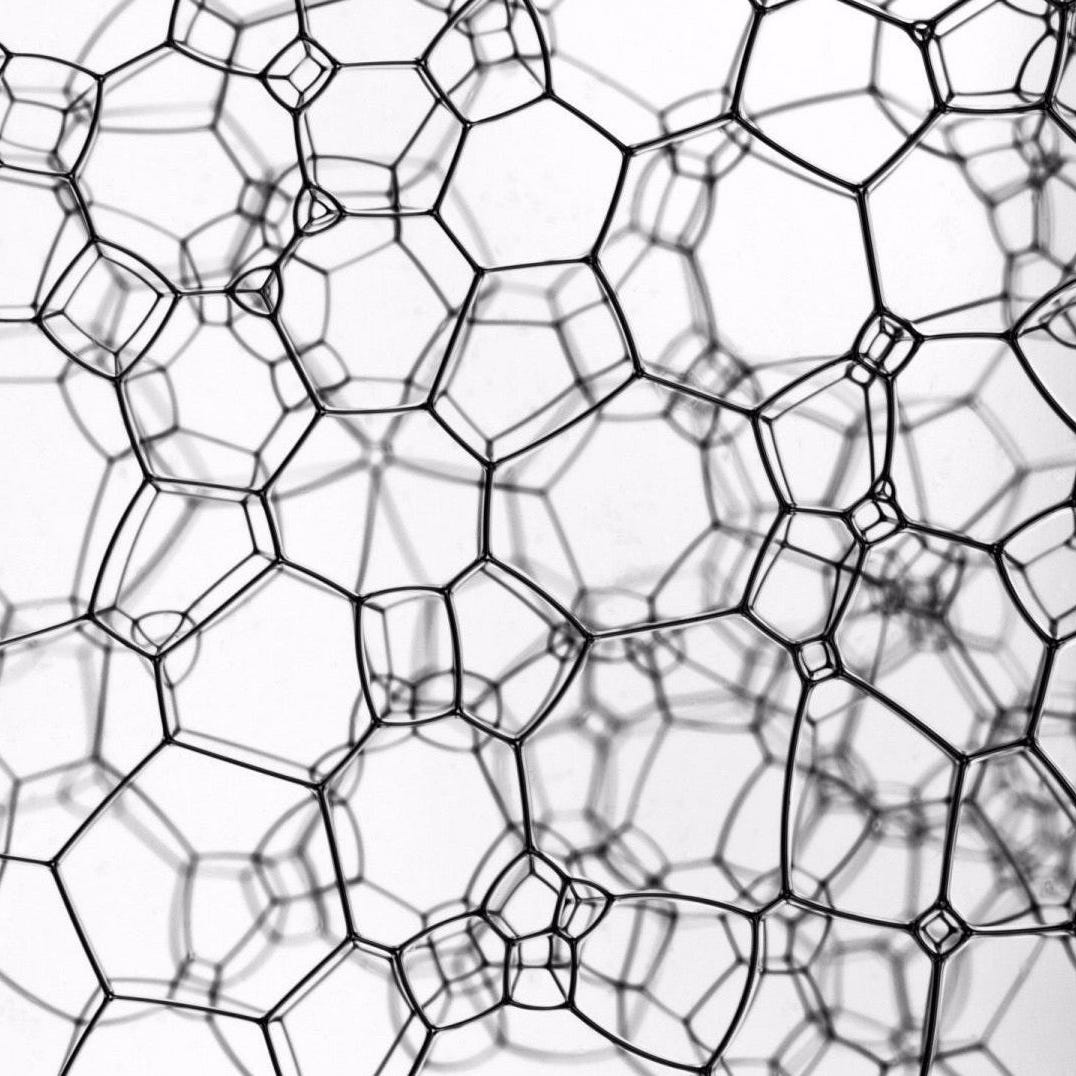

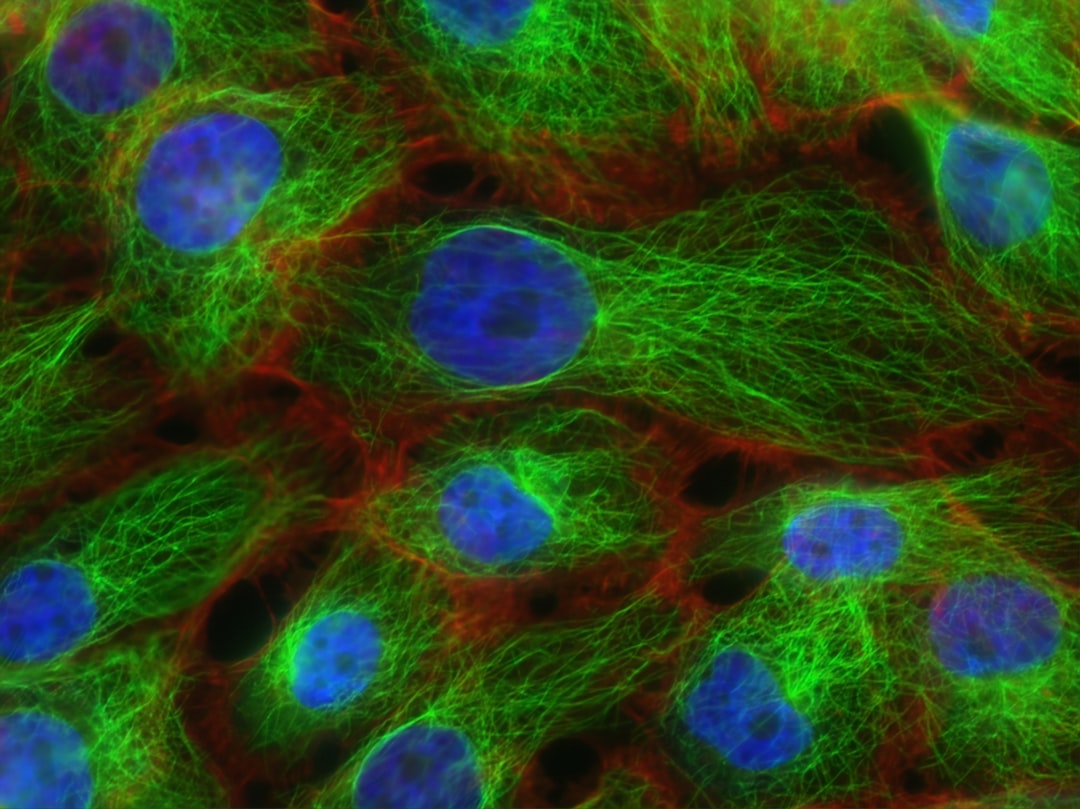

Innovation: How Management Must Change in an Emergent Discovery Culture

I recently wrote about Flagship Pioneering’s breakthrough approach to innovation: Emergent Discovery, as Noubar Afeyan and Gary P. Pisano characterize it:

a rigorous set of activities including prospecting for ideas in novel spaces; developing speculative conjectures; and relentlessly questioning hypotheses.

Emergent discovery starts with prospecting for potentially important ideas in relatively novel scientific, technological, or market spaces with the goal of generating speculative conjectures, or “what if” questions. These serve as the starting point for an intensive Darwinian-style selection process to find and validate better ideas, soliciting critical feedback from outsiders to identify challenges and evolving the concept into a superior and practical solution.

The authors raise the question I want to address here, the cultural side:

Emergent discovery requires a culture in which people, particularly leaders, in an organization are comfortable broaching seemingly infeasible ideas and challenging dogma—a culture that views “flawed” ideas not as dead ends but as building blocks and considers the evolution of ideas to be a collectively shared responsibility.

The authors state that there are three critical leadership behaviors for emergent discovery to work, each of which is likely to be a challenge for traditional, linear management:

1 | Make it acceptable to broach the unreasonable — As the authors restate it, ‘to foster emergent discovery in your organization, you need to make it acceptable to consider the seemingly impossible’. Participants should avoid questions (and attitudes) that are close-ended, like “Why do you believe that’, which tend to shut down the process of inquiry.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Work Futures to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.