All Are Responsible

Abraham Joshua Heschel | Art, Sport, or Extinct | Factoids

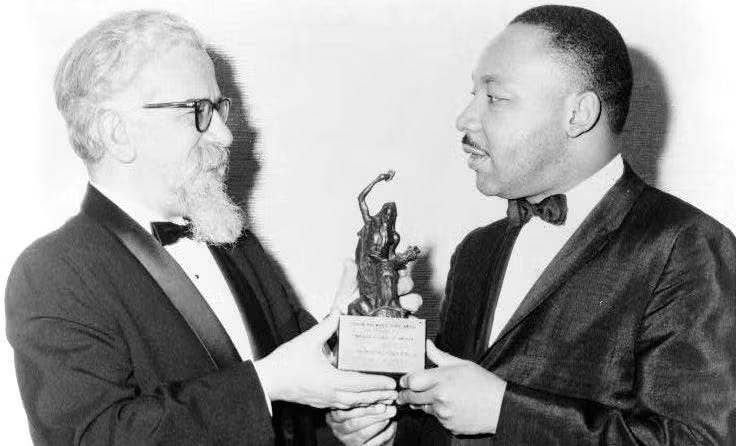

In a free society, all are involved in what some are doing. Some are guilty; all are responsible.

| Abraham Joshua Heschel

…

I won’t take the bait of arguing about exactly how free our society is these days. But Heschel makes a compelling point: we can’t isolate ourselves from others' actions by claiming innocence or pretending to be uninvolved. In particular, when people are doing wrong, we are compelled to intervene to address that wrongdoing.

My focus here at workfutures.io is the world of work, but, as I have stated many times before, work touches everything. And everything touches work.

I am not a dispassionate observer or a scientist driven by supposed professional neutrality. Instead, my opinions are arguments are grounded in an agenda shaped by economics and moral philosophy.

Therefore, I feel I have to call out the business trends that are — at their core — counter to humanism, and contribute to pushing the world out of balance.

As Claude Lévi-Strauss said,

A well-ordered humanism does not begin with itself, but puts things back in their place. It puts the world before life, life before man, and the respect of others before love of self.

I maintain that Lévi-Strauss was talking about a world in balance. And those that promote business practices and political economies that push the world out of balance are the ‘guilty’ ones that Heschel was speaking of. And we, all of us, are the ‘responsible’ ones. The answer must be to take action against them.

Art, Sport, or Extinct

Alex Dobrenko recently interviewed Anu Atluru, someone whose writing I have admired in the past. However, in this instance, she embodies an attitude toward the embrace of AI that has become increasingly common in tech and business circles, one that trivializes the danger of an economy dominated by AI in every nook and cranny of work.

Anu Ataluru: The question I keep returning to is: what do we actually want people for? In the past, we wanted them for labor, efficiency, and technical skills. Now, we want them for that, but we also want them for more interpersonal things. The test is: would I rather work with this person—or work alone with better tools? That will determine if they’ll be in my small crew. Which is a long-winded way of saying, even with all this tech, I still want a teammate.

That seems like a positive check on the rise of AI, so long as people get to choose who to work with for themselves.

I wrote about this question 10 years ago:

The central question of 2025 will be: What are people for in a world that does not need their labor, and where only a minority are needed to guide the ‘bot-based economy?

Atluru seems to imagine a future where knowledge workers (at least) will a/ still have jobs and b/ they will choose whether to work with other people or AI.

Alex Dobrenko: Yeah, it’s also a societal question of whether we, as people, will want to work with each other or with a tool.

Anu Atluru: Right. I think in some cases, we’ll want to get out of the face of tools. We’ve seen this before, even before we called it AI, with the automation of call centers, customer support, and even self-checkout at the grocery store. In some of those cases, we’re okay not having a human there. In other cases, we want someone there.

Note that the ‘we’ Atluru alludes to are the customers making the support calls, and buying the groceries. She doesn’t talk about the people who have lost their jobs to automation — they’ve been elided from the conversation [emphasis mine]:

I have this framework in my mind that as we go forward on this automation / AI curve, every human skill will either become extinct, art, or sport.

Extinct when machines absorb it. Art when humans still do it because we care about the person, story, or meaning. Sport when we watch humans test their limits — often for its own sake.

This ‘extinct, art, or sport’ categorization is the thread in this discussion that inspired me to write this. I’m fine with people whose vocation rises to the level of art, as most of us are. Likewise, ‘athletes’ in the broadest sense, who strive in any domain, as with sports. I accept the idea that the greatest artists and athletes command and receive generous rewards for their work.

It’s the extinction of lines of work that especially concerns me, and should concern anyone thinking of the economy and the people who make it up. I am terrified of enormous disruptions in work, and the consequences for those directly impacted.

As just one example, there are 3.6 million truck drivers working in the US as of 2023. Consider the implications as AI begins to handle more of that driving. Many of those jobs are quite well-compensated — Owner-Operators gross $320,980 on average, and that Carvana car hauler averages $97,639 — and driverless trucks could displace — make extinct — an entire middle-class occupation. And few truck drivers are likely to be elevated to the level of artists or sports heroes.