Long Time Coming

Rudi Dornbusch | Wishcasting | Reverberations of the Donut Effect | Reading

Quote of the Moment

The crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought.

| Rudi Dornbusch

Word of the Day: Wishcasting

Noun. wishcasting

The act of interpreting information or a situation in a way that casts it as favorable or desired, despite the fact that there is no evidence for such a conclusion; a wishful forecast.

2020, Sarah Longwell, What Did They Think Would Happen?, in The Bulwark:

We have an incurious narcissist of a president who was warned over and over by his advisors about an imminent pandemic. He ignored them. Then he engaged in “one day it will just disappear” wishcasting instead of spearheading a coordinated federal response.

2024, Joe Fassler, Cultivated Meat’s Empty Promise of Revolution, in The New York Times:

As familiar as cultivated meat’s bumpy trajectory may be, one thing stands out: The industry, and in particular, its two biggest players, Upside Foods and Eat Just, built expensive facilities and pushed for government approval before they had overcome the most fundamental technological challenges.

At a cellular agriculture summit last month at Tufts, a biotech expert, Dave Humbird, said the industry had “wishcast” its way to market readiness, something he’s never seen work. His prediction for the future of cultivated meat: “R & D will go back into academia. And that’s probably a good thing.”

His extensive analysis in the peer-reviewed journal Biotechnology and Bioengineering found that the costs of production at cultivated meat facilities would “likely preclude the affordability of their products as food.”

There’s a lot of wishcasting going on, everywhere you look or listen.

Reverberations of the Donut Effect

In early 2021, the economists Arjun Ramani and Nicholas Bloom released a paper entitled The Donut Effect of Covid-19 on Cities. The authors analyzed various sources of data to shed light on the impact of the pandemic — and the rapid rise of remote work — on where people were living. They define the effect this way:

Our first result is that real estate demand as measured by rents or prices reallocates away from major city centers towards lower density areas on the outskirts of cities in a phenomenon we call the “donut effect”.

In a nutshell, in the first of the two major impacts of Covid on migration and real estate markets, given the opportunity to do so, many people migrated to the periphery of large superstar cities away from the donut hole — the urban core — out to the suburbs and beyond. This is the direct consequence of not having to commute to the office every day… or not at all, in some cases.

The effect seemed limited to large cities:

This donut effect is primarily a large city phenomenon. Outside of the twelve largest metro areas by population, we do not observe much price growth divergence or difference in population or business outflow between the CBD and lower density zip codes. The donut effect is more widespread when measured through rents but is still primarily a large-city phenomenon. The top 12 cities as measured by population see the strongest donut effects, the next 13-50 cities see smaller effects, while the remaining 51 to 365 cities see little to no effects.

The second major impact the authors researched was the range of the migration. At that time, it seemed that the donut effect was localized. At least at the time of their study, there wasn’t a mass movement from superstar cities’ environs to smaller cities:

Though we observe a within-metro reallocation in economic activity, we observe much less between-metro reallocation in activity. Indeed, metro-level regressions show that price growth was actually stronger in denser metros. Change-of-address data on the other hand show some movement across metros from denser metros to sparser metros, but this movement is quantitatively small relative to the within-metro movement from city centers to their suburbs. Overall, this finding suggests that the rise of so-called “Zoom Towns”, smaller cities across America that have been marketed as remote work hubs, may not represent a broader long-term trend in the data.

Now in 2024, we can look back and see that the second factor has shifted, based on using different data. For example, San Francisco saw large out-migration in 2019 and 2020:

San Francisco lost the most residents between 2019 and 2020 out of every major city, according to a new analysis.

The Bay Area city lost about 18 residents per 1,000 people in 2020, compared to losing just 9 residents out of ever 1,000 the year prior, according to a new report by the commercial realty firm CBRE Group.

Though most people moved out of San Francisco to other areas in California, the share of people moving to Texas and Florida soared compared to 2019, the data showed. The number of people who moved from San Francisco to Texas increased by 32.1% between 2019 to 2020, and the share of those who moved to Florida rose by a whopping 46.2%.

Once remote/hybrid becomes the norm, people hollow out the urban core, and that may include moving to lower-density, lower-cost cities far from their original location.

And we are seeing the reverberations of the enormous behavioral and demographic shift in — no surprise — the superstar cities that are suffering this outmigration.

McKinsey researchers have written an 88-page report on the impact of remote work on superstar cities globally. The top-level findings:

Office attendance has stabilized at 30 percent below prepandemic norms.

Untethered from their offices, residents have left urban cores and shifted their shopping elsewhere.

In a moderate scenario that we [McKinsey] modeled, demand for office space is 13 percent lower in 2030 than it was in 2019 for the median city in our study. In a severe scenario, demand falls by 38 percent in the most heavily affected city.

Demand may be lower in neighborhoods and cities characterized by dense office space, expensive housing, and large employers in the knowledge economy.

Cities and buildings can adapt and thrive by taking hybrid approaches themselves. Priorities might include developing mixed-use neighborhoods, constructing more adaptable buildings, and designing multiuse office and retail space.

The hard numbers by KcKinsey:

During the pandemic, a wave of households left the urban cores of superstar cities, and fewer households moved in. For example, New York City’s urban core lost 5 percent of its population from mid-2020 to mid-2022, and San Francisco’s lost 7 percent. The main reason was out-migration. In the suburbs, by contrast, populations grew, or they shrank less dramatically than populations in the urban cores did. In the United States, suburbanization had already been happening before the pandemic, and the shock accelerated an existing trend; by contrast, in most of the European and Japanese cities we studied, urbanization gave way to suburbanization.

McKinsey spins some scenarios, and this is a moderate one, where, for example, New York Office Space declines by 16% between 2019 and 2030.

They contrast that with this:

In a more severe scenario, in which attendance for all office workers in 2030 falls to the rate already seen in large firms in the knowledge economy, demand is as much as 38 percent lower than it was in 2019, again depending on the city.

But, after amassing a great deal of data, the McKinsey research fails the sniff test and falls into wishcasting: too much of their hopes for an urban core turnaround is based on utopian ‘congenial city’ tropes. For example, this:

One way cities could adapt is through mixed-use neighborhoods—that is, neighborhoods that are not dominated by a single type of real estate (especially offices) but instead incorporate a diverse mix of office, residential, and retail space.

Such hybrid neighborhoods were becoming more popular even before the pandemic. And now that the pandemic has reduced demand for offices, cities have been left with vacant space that could be converted to other uses.

They note elsewhere that converting office buildings to residential use will encounter many barriers: zoning, neighborhood buy-in, architectural challenges, and high cost. That doesn’t seem to slow their enthusiasm.

Furthermore, our research shows that mixed-use neighborhoods have suffered less during the pandemic than office-dense neighborhoods have. That resilience gives investors, developers, and cities still more reason to engage in placemaking.

Redeveloping neighborhoods is an enormous undertaking, of course, so mobilizing the many stakeholders is important. Governments may be particularly helpful in reforming restrictive zoning policies. Investors would be needed to finance redevelopment. And developers would be the ones to turn mixed-use visions into realities.

Recent controversies in New York suggest that the path to a multiuse nirvana for these emptied-out cities -- devastated by the Donut Effect — will be steep and rocky at best and may not be in the cards in the timeframe they focus on: between now and 2030.

The most glaring omission: They don't mention transportation as a key aspect of the urban core and how better connections across the urban core, the suburbs, and the periphery could benefit people across the board. Making it easier to commute makes it easier to entice people into the city core and allows people to move farther out, too.

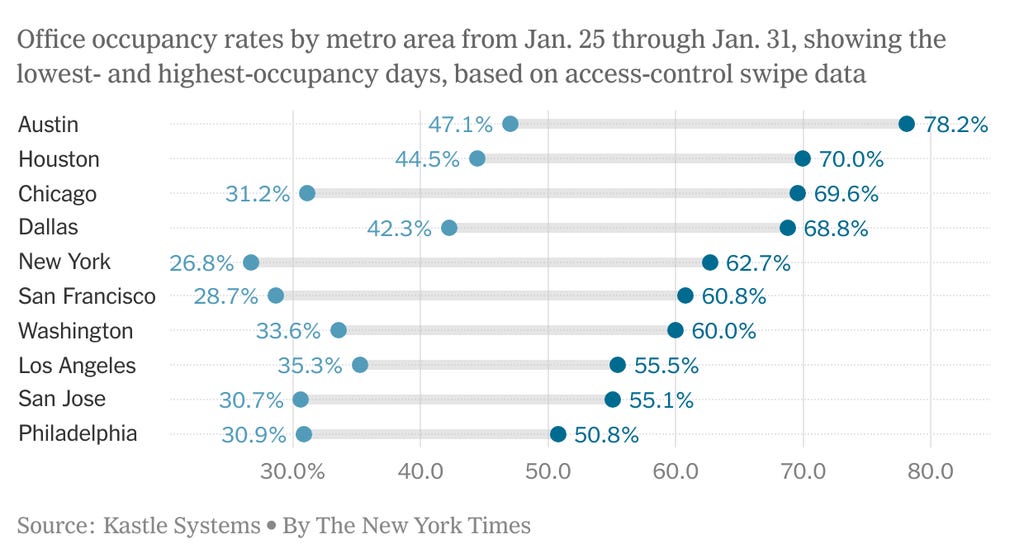

Peter Coy looked at the KcKinsey report and spoke with some experts. The biggest impact of the donut effect is already being felt in New York City, where occupancy has fallen to as low as 27% on some days, and maxes out in the low 60s!

The low occupancy rate is a ticking time bomb for owners of office buildings. When leases expire, tenants won’t want as much space as they have now. Vacancy rates will shoot up. We’re already seeing that happen. Last month Moody’s Analytics announced that the national office vacancy rate rose in the fourth quarter to 19.6 percent, breaking the record of 19.3 percent that was set in 1986 after a period of overbuilding and was then tied in 1991 during the savings and loan crisis.

The possible impacts of the commercial real estate market bottoming out are looming:

“The office market has an existential crisis right now,” Barry Sternlicht, the chief executive of Starwood Capital Group, an investment firm focused on real estate, said at the iConnections Global Alts 2024 conference last week, according to a Reuters report. “It’s a $3 trillion asset class that is probably worth $1.8 trillion. There’s $1.2 trillion of losses spread somewhere, and nobody knows exactly where it all is.”

[…]

Many building owners refinanced their debt when the Federal Reserve slashed interest rates to combat the Covid downturn. Their debt expenses are likely to skyrocket when their loans mature between now and roughly 2028. The Fed is planning to cut rates this year, but that will leave them still well above prepandemic levels. Goldman Sachs calculated in November that about a quarter of commercial mortgages are scheduled to mature this year and next barring extensions, the highest percentage since its records began in 2008.

So, a huge surge in refinancing in the next two years, when real estate owners will take on burdensome higher loans… or walk away, leaving the banks with empty office buildings they don’t want and can’t sell.

Coy pointed out that the commercial real estate market is jittery:

Investors’ fears were awakened last week when New York Community Bancorp, which is exposed to commercial real estate, including office buildings, reported a $252 million quarterly loss. Its stock lost 60 percent of its value from Jan. 30 through Tuesday. The S&P Composite 1500 index of U.S. regional banks fell sharply over concerns about the banks’ exposure to losses in commercial real estate, particularly office buildings. Real estate investment trusts in the office sector also fell.

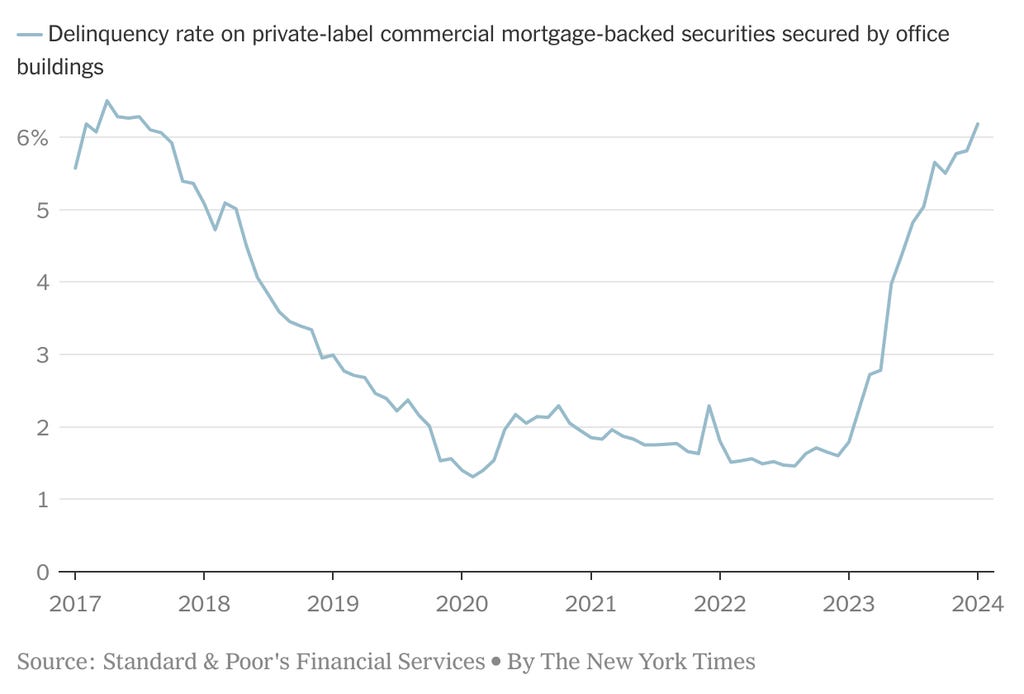

Delinquencies on private-label commercial mortgage-backed securities on office buildings still aren’t historically high, but they’re back to where they were in 2017, as this chart based on data from Standard & Poor’s Financial Services shows.

Conclusions

The takeaway is simple. The shift to remote and now hybrid work led to a donut effect, and the second-order impact of this hollowing out of the urban core of superstar cities is now being felt in the commercial real estate markets of those cities.

Dewey-eyed wishcasting about a utopian multiuse future for these cities won’t will them into existence. The challenges are enormous, and those entrusted with the future of these cities and our economy may propose hypothetical programs to avoid the most severe consequences of inaction, but very little is actually being accomplished. Meanwhile, that $1.5 trillion in potential losses is still unaccounted for, but the bill is going to come due this year or next.

The deepest problem is that cities will need to cut their budgets as property tax and other sources of revenue dry up, and that will accelerate the urban doom loop: less tax money, fewer services, the city grows less attractive, more move away, real estate values fall, and so on.

Something significant has to change to disrupt the downward spiral. And soon.

Remember Dornbusch’s rule.

Reading

I received a copy of Post-Work edited by Stanley Aronowitz and Jonathan Cutler. I was introduced to Aronowitz by Kathi Week’s The Problem With Work, where he and co-author William DiFazio were quoted:

The quality and the quantity of paid labor no longer justify— if they ever did— the underlying claim derived from religious sources that has become the basis of contemporary social theory and social policy: the view that paid work should be the core of personal identity.

Stay tuned.

…

A paper by Chinchih Chen, Carl Benedikt Frey, and Giorgio Presidente, entitled Disrupting Science, appears to provide evidence that as ‘coordination have fallen with recent advances in ICT [video conferencing, work chat etc.]. Indeed, exploring the relationship between geographical dispersion and disruption decade by decade, we find evidence that [the correlation between colocation of researchers and greater innovation in research teams] reversed in recent years, suggesting that the benefits of colocation may have declined over time.’

More to follow.