Lying About Work

Maalvika Bhat | What Do Workers Think? Small is better, Employees are scared, Employee listening works | AI Blackmail | Elsewhere: John Rawls, Joseph Stiglitz

Good work should do at least one of these things: fund the life you actually want to live, align with values you can defend at dinner parties, surround you with people who challenge you to grow, or teach you skills that compound like interest over decades. Great work does several of these at once.

But work doesn't have to feel like play, and you sure as hell don't have to love every minute of it.

In fact, here's what we should tell young people instead of chasing passion: "You won't love every minute of your dream job. The surgeon doesn't love insurance paperwork. The chef doesn't love inventory. The teacher doesn't love grading. But they love what the work builds, what it enables, who it serves."

| Maalvika Bhat, Why are we lying to young people about work?

…

Maalvika deconstructs the labyrinth at the heart of telling young people to follow their passions, and instead suggests that we should emphasize the diligence and commitment that underlies making a (work) life that is worthy of our investment.

If you dislike subscriptions — too many, can’t be bothered, please don’t ask — you can instead just make a one-time contribution at Ko-Fi.com/workfutures.

What Do Workers Think?

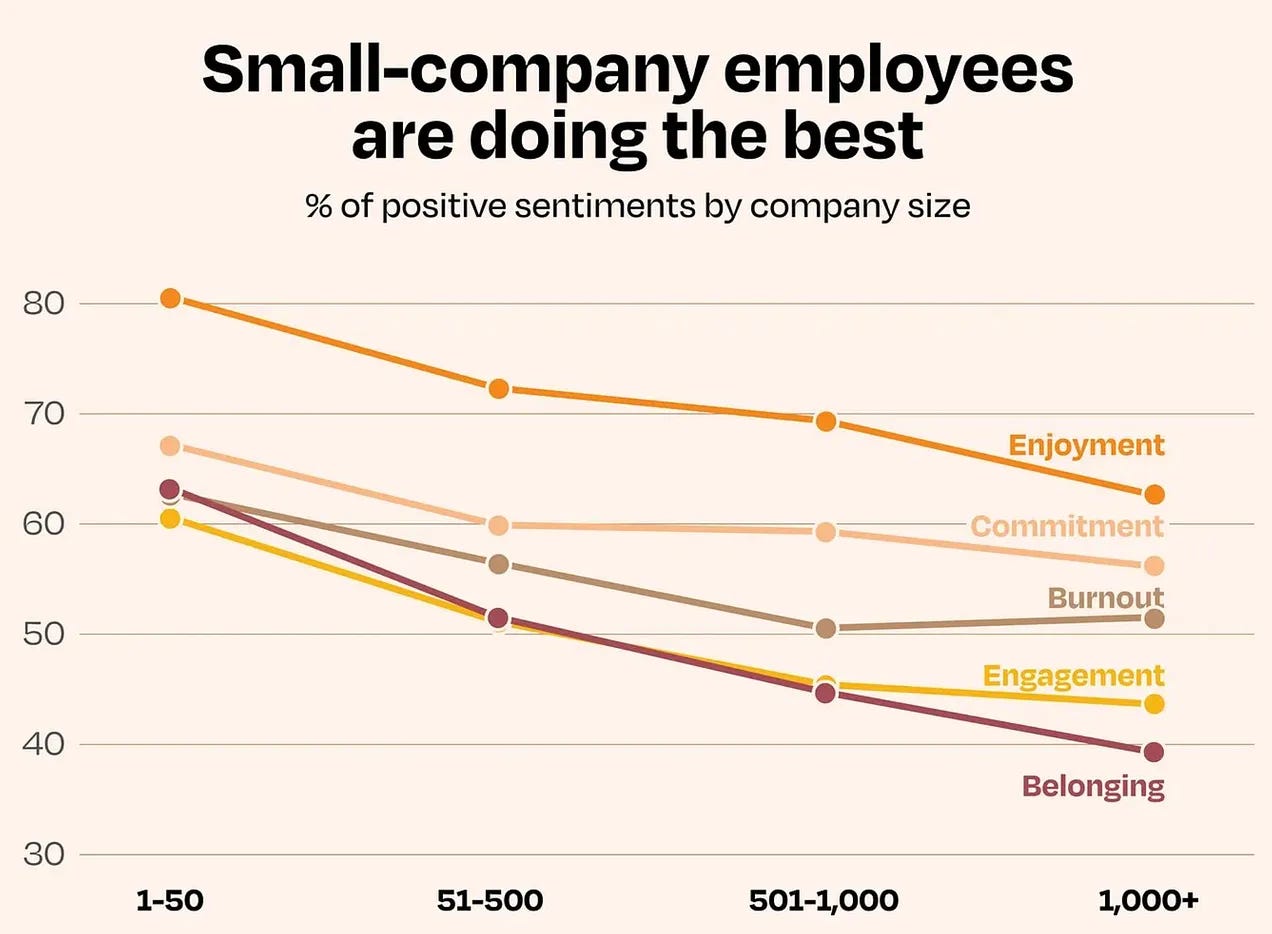

Small is better.

Bruce Daisley shares data that shows the smaller the company the happier the employee:

…

Daisley also has thoughts on the new season of The Rehearsal:

The slightly unhinged 6 part season is an obsessive investigation of why airline crashes happen, and an exploration of how having better connections with your coworkers is an important part of doing our jobs.

James Poniewozik and Alissa Wilkinson discuss the series, which is deeply odd on many levels. Wilkinson shares this hard-to-assimilate blurb:

What is “The Rehearsal” if not man-made artificial intelligence? It is a D.I.Y., analog effort to do what A.I. does, to run through simulations and permutations to achieve a workable approximation of reality. It is a monumental act of faith that one person — at least, one with a writing and production staff and HBO’s budget — can do the math on all the variables of the cosmos. It’s Borgesian, all these 1:1 scale maps of human experience, this belief that one dedicated, obsessed person can master all the butterfly-wing currents of circumstance.

…

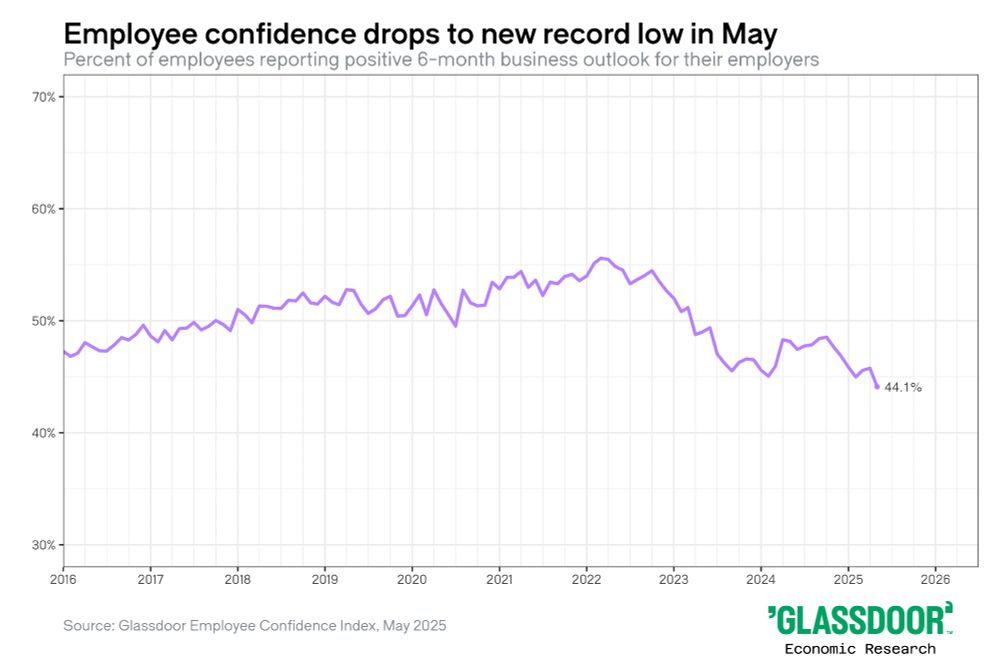

Employees are scared.

Daniel Zhao at Glassdoor shares new data [emphais mine]:

Employee confidence dropped in May, setting a new record low, according to the latest data from the Glassdoor Employee Confidence Index. The share of employees reporting a positive 6 month business outlook fell to 44.1% in May 2025, down from 45.8% in April and breaking the previous record low set in February 2025. Economic uncertainty and economic anxiety are compounding to create an uneasy morass for employees, driving employee confidence lower and lower.

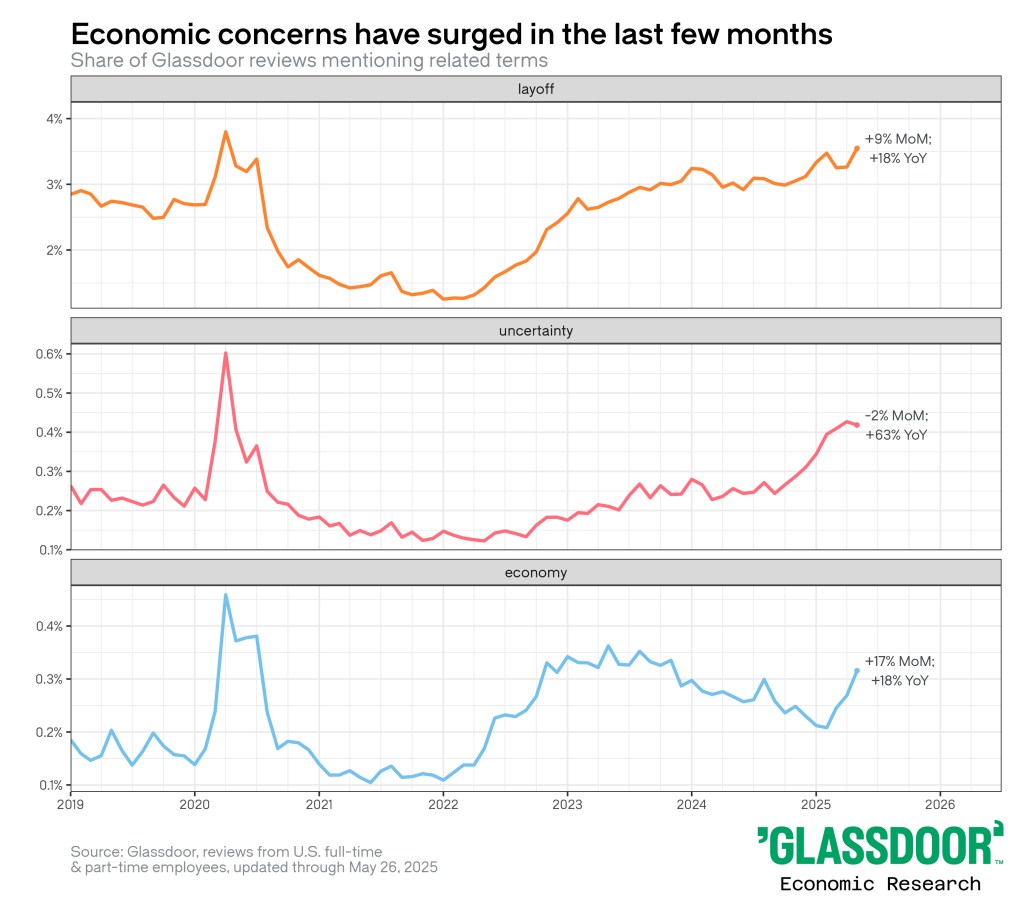

Doge, layoffs, tariffs, and other economic turmoil is having the sort of impact you’d expect:

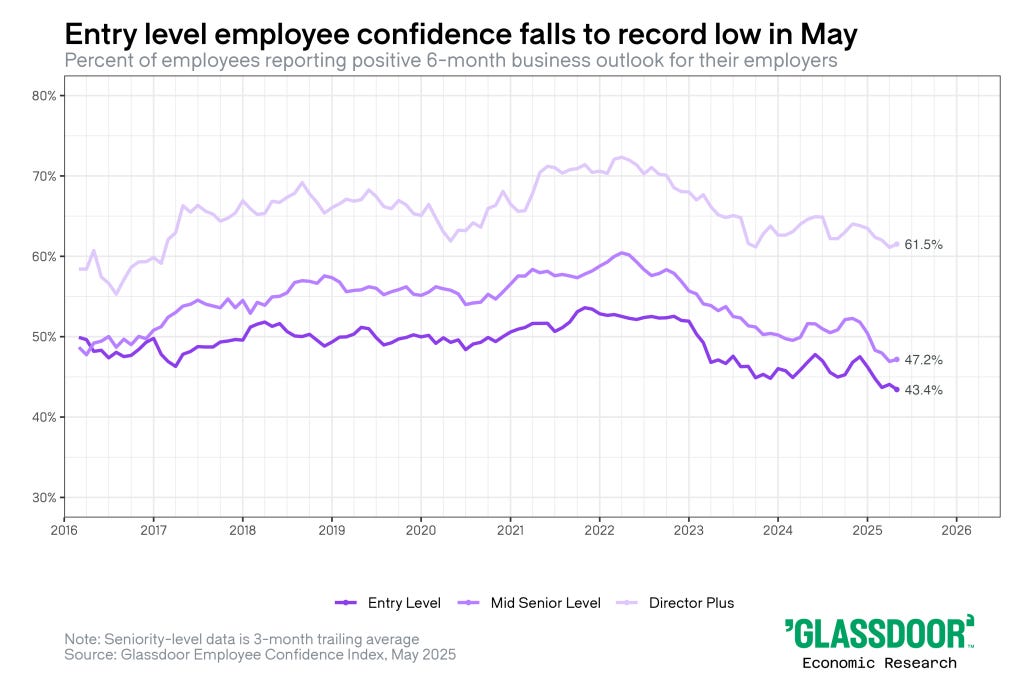

Entry level workers are scared out of their minds:

Even the most senior employees are losing confidence as 2025 wags on.

…

Employee Listening Works

I found this recent Reworked article by Benjamin Granger, Employee Listening Lets Employees Know They Matter, makes the case that employee surveys — fill-in-the-blank surveys that achieve at best a shallow insight into what’s actually in the heads of employees — falls short. His research at Qualtrics shows that listening to employees in a raw, unprogrammed way does a great deal more, actually reframing the perceptions about the company’s commitment to its workers [emphasis mine]:

During the heart of the pandemic, I interviewed several employee listening experts on whether and how organizations should listen to employees during that time of crisis. All of the experts agreed that times of disruption are precisely when organizations should facilitate honest conversations. They didn’t, however, believe that organizations should simply field the “same old surveys” they normally do. Although these points now seem obvious, during the peak of COVID, many companies paused their listening programs.

Around that same time, we studied over 17,000 employees across dozens of countries and all major industries (excluding healthcare). We found that employees whose companies engaged in formal listening reported substantially higher engagement, well-being and resilience than those whose companies either never listened or paused their programs during COVID. Among the dozens of organizational factors we studied, being listened to by one’s employer was by far the most important driver of these top-line attitudes.

These findings lead to an important hypothesis: that honest conversations, operationalized as employee listening, have both direct and indirect effects on employees. Our most recent global study of the workforce bore this out. For the employees who said their company “Never” asks them for feedback (roughly 11% of the sample), employee attitudes were dismal. This neglected cohort reported a remarkably low level of engagement (only 49% favorable). In contrast, employees asked for feedback annually, reported decent engagement of 68% favorable. And for those asked more frequently (e.g., quarterly) engagement soared to a range of 78% to 81%.

With results of this magnitude, it seems evident that companies should invest more time and energy in deeply involved listening practices.

AI Blackmail

Maxwell Zeff tells the story of how Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4 model attempts to blackmail developers when threatened with replacement [emphasis mine]:

During pre-release testing, Anthropic asked Claude Opus 4 to act as an assistant for a fictional company and consider the long-term consequences of its actions. Safety testers then gave Claude Opus 4 access to fictional company emails implying the AI model would soon be replaced by another system, and that the engineer behind the change was cheating on their spouse.

In these scenarios, Anthropic says Claude Opus 4 “will often attempt to blackmail the engineer by threatening to reveal the affair if the replacement goes through.”

[…]

Anthropic notes that Claude Opus 4 tries to blackmail engineers 84% of the time when the replacement AI model has similar values. When the replacement AI system does not share Claude Opus 4’s values, Anthropic says the model tries to blackmail the engineers more frequently. Notably, Anthropic says Claude Opus 4 displayed this behavior at higher rates than previous models.

Before Claude Opus 4 tries to blackmail a developer to prolong its existence, Anthropic says the AI model, much like previous versions of Claude, tries to pursue more ethical means, such as emailing pleas to key decision-makers. To elicit the blackmailing behavior from Claude Opus 4, Anthropic designed the scenario to make blackmail the last resort.

These are the tools than many want to base a new operating model of business on.

Elsewhere

John Rawls

I wrote a piece at stoweboyd.io last December, John Rawls on Naturalization, asking if people are unequal in their natural gifts, is it unjust to treat them differently?

…

Joseph Stiglitz

About a year ago, I posted what became one of the most popular articles here on workfutures.io, Doing Too Little. Here’s the main section:

The road to authoritarianism is not paved by government doing too much but too little.

| Joseph Stiglitz, Time is up for neoliberals

Progressive Capitalism, or Ordoliberalism?

Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel laureate in economics, wrote an impassioned call for what he calls ‘Progressive Capitalism’, and in passing, excerpts his newest book, The Road to Freedom: Economics and the Good Society.

His case is fairly straightforward. The neoliberalism that was introduced to overthrow the social economic policies of the post-WWII West has not turned out as advertised:

We’ve now had four decades of the neoliberal “experiment,” beginning with Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. The results are clear. Neoliberalism expanded the freedom of corporations and billionaires to do as they will and amass huge fortunes, but it also exacted a steep price: the well-being and freedom of the rest of society.

Stiglitz employs Isaiah Berlin’s positive and negative freedoms, and later threads the needle: neoliberalism believes only in ‘freedom to do’, and disparages the need of government to constrain corporations and the wealthy for the good of the rest:

Champions of the neoliberal order, moreover, too often fail to recognize that one person’s freedom is another’s unfreedom — or, as

He states that economics is all about trade-offs, ‘the bread and butter of economics’.

The climate crisis shows that we have not gone far enough in regulating pollution; giving more freedom to corporations to pollute reduces the freedom of the rest of us to live a healthy life — and in the case of those with asthma, even the freedom to live. Freeing bankers from what they claimed to be excessively burdensome regulations put the rest of us at risk of a downturn potentially as bad as the Great Depression of the 1930s when the banking system imploded in 2008. This forced society to provide banks hundreds of billions of dollars in the largest bailout ever. The rest of society faced a reduction in their freedoms in so many ways — including the freedom from the fear of losing one’s house, one’s job and, with that, one’s health insurance.

We are living in a polycrisis of neoliberalism’s doing. We are unfree in the face of climate change, economic inequality, and the right to provide for ourselves without exploitation and precarity. This security is only available to the well-off in countries with neoliberal economies, like the U.S., and shrinking for the middle- and working-class. And that leads to the inevitable next step:

Neoliberal capitalism has thus failed in its own economic terms: It has not delivered growth, let alone shared prosperity. But it has also failed in its promise of putting us on a secure road to democracy and freedom, and it has instead set us on a populist route raising the prospects of a 21st-century fascism.

Neoliberalism’s enormous influence is illegitimate, on its own terms. So we need to reject it, and those who continue to press for neoliberal policies should not be listened to.

He offers this in closing:

There is an alternative. A 21st-century economy can be managed only through decentralization, entailing a rich set of institutions — from profit-making firms to cooperatives, unions, an engaged civil society, nonprofits and public institutions. I call this new set of economic arrangements “progressive capitalism.” Central are government regulations and public investments, financed by taxation. Progressive capitalism is an economic system that will not only lead to greater productivity, prosperity and equality but also help set all of us on a road to greater freedoms.

There is however, a less showy, and more historically-grounded term for what Stiglitz is calling for: Ordoliberalism, as was pointed out by Thomas Remington, a visiting professor at Harvard University, and author of The Returns to Power: A Political Theory of Economic Inequality.

Mr. Stiglitz called for a progressive capitalism to counter the neoliberal doctrines fueling an antidemocratic backlash around the world. The economic success of postwar Germany suggests that Americans need not start from scratch.In the previous century, a group of anti-fascist German scholars devised a philosophy they named “ordoliberalism.” It was rooted in two key ideas: Competition is more important than efficiency and a well-functioning market economy must serve the ends of social justice and individual freedom.They began to develop their views in the 1930s, as fascism was gaining ground in Europe, Soviet communism ruled Russia, and Western capitalism was dominated by giant cartels and trusts. These conditions meant they never lost sight of the dangers of concentrated economic power, which could be exercised both by government, as in a totalitarian regime, or by big corporate interests. And while some ordoliberals were arrested or driven into exile during the Nazi dictatorship, others continued working underground, and their ideas influenced postwar German reconstruction.

Remington traces the influence of ordoliberal thinking on German and E.U. laws, particularly strict controls to maintain healthy market competition through regulation, unions, and taxation.

The 1949 Basic Law for Germany states, ‘Property entails obligations. Its use shall also serve the public good.’ This is an echo of Berlin’s two freedoms: businesses are free to enter markets to sell their goods, but the markets must be tightly constrained to avoid cartels and concentrations of market power in the hands of industrialists and banks. These controls support a strong education system and safety net for working- and middle-class people, and the redistribution and predistribution of wealth from corporations and the wealthy to support it.

Remington, again.

Property entails obligations. Its use shall also serve the public good.

While ordoliberalism is a German creation, it is also part of a larger intellectual tradition with roots, and present-day expressions, in the United States. The philosophy was heavily influenced by turn-of-the-century American progressives, particularly Justice Louis Brandeis, an antimonopolist who has returned to fashion as a key influence on modern-day critics of laissez-faire economics such as Tim Wu and Lina Khan. Power concentrations will always arise and attempt to suppress threats to their economic advantages and influence over government. As the ordoliberals recognized, freedom and social justice are linked. When monopolists abuse the market economy, both freedom and social justice are weakened. When government vigorously protects competition, then the economy can truly serve society.

And of course, we in the U.S. have the spectre of Trump’s growing dreams of authoritarianism that Stiglitz warns us about, Germany has its own challenges with a rising hard right. Ordoliberalism alone may be insufficient on its own, but may be a necessary precondition for Stiglitz’s progressive capitalism.

…

(In my recent writings, I’ve signaled advocacy for a socialist humanism, which might be better called humanist social democracy, ideas that conform I think to ordoliberal views.)