Not In A Hurry

Stucktopia | Is Ghosting better than Love Bombing? | Time Confetti | Factoids | Elsewhere

Nature is not in a hurry, yet everything is accomplished.

| Lao Tzu

…

In the hustle-bustle of everyday affairs, it is easy to overlook the inexorable transitions of nature. At the most fundamental layers, things are slow to change, although change they will.

At the same time, at more changeable layers of human society, like entertainment, politics, and popular sentiment, things have never seemed more frenzied. And at intervening layers, change grinds, layer by layer, through institutions, belief systems, and culture, slowing and speeding, sometimes smoothly, often in fits and starts, and feeling chaotic.

It’s difficult to retain a Taoist acceptance of ‘not in a hurry’ when confronted by what seem to be circumstances calling out for rapid change. One effect of that conflict within us is feeling stuck. Hillary Kelly brought this into sharp clarity for me this week, in her turn-of-phrase ‘stucktopia’.

Stucktopia

In Welcome to Stucktopia, Hillary Kelly performs that most dangerous trick: coining a new word, which William James pointed out was undertaken 'at one’s own peril'. In Kelly's case, the word is stucktopia, which she argues is where we are now:

The hallways on the television shows I watch have been driving me mad. On one sci-fi show after another I’ve encountered long, zigzagging, labyrinthine passageways marked by impenetrable doors and countless blind alleys — places that have no obvious beginning or end. The characters are holed up in bunkers (“Fallout”), consigned to stark subterranean offices (“Severance”), locked in Escher-like prisons (“Andor”) or living in spiraling mile-deep underground complexes (“Silo”). Escape is unimaginable, endless repetition is crushingly routine and people are trapped in a world marked by inertia and hopelessness.

The resonance is chilling: Television has managed to uncannily capture the way life feels right now.

We’re all stuck.

What’s being portrayed is not exactly a dystopia. It’s certainly not a utopia. It’s something different: a stucktopia. These fictional worlds are controlled by an overclass, and the folks battling in the mire are underdogs — mechanics, office drones, pilots and young brides. Yet they’re also complicit, to varying degrees, in the machinery that keeps them stranded. Once they realize this, they strive to discard their sense of futility — the least helpful of emotions — and try to find the will to enact change.

The stucktopia might seem resonant to you, too. Time is a flat circle. The same two political candidates are running for president, while parodic commentary is once again being provided by Jon Stewart, who first hosted “The Daily Show” in 1999. Congress produces little more than increasingly outlandish sound bites. There are protests nearly every day, yet no resolution or change. Mass culture has come to a standstill, with endless reboots and resuscitations. Thanks to knockoff mania and fast fashion, clothes and décor look like copies of copies. We spent a pandemic locked up in our homes, and the outside world — with superstorms and deadly heat waves — is no longer the respite Thoreau once envisioned. If we retreat into our phones, we end up algorithmically chasing ourselves down familiar rabbit holes.

Pop culture, performing its canary-in-the-coal-mine function, has been trying to warn us about stucktopia. Every age gets the dystopian nightmares it most fears: In the 1930s and ’40s, it was George Orwell and Aldous Huxley’s visions of totalitarianism; at the millennium, it was dark imaginings of societal collapse, whether a zombie apocalypse or the hunger games. Our new fictional nightmares are all about being trapped: mice running in an endless maze, too cowed by the complexity of the system to plow through the dead ends and find freedom.

Televised portrayals of stuckopia can’t defeat authoritarian governments or teach us how to do so ourselves. But they do offer a first step toward action — a way to recognize what parts of us are purposely staying stuck. Considered together, these shows force us to consider whether we’ll stay content with our meager daily doses of cold comfort in a larger, broken system — or toss them aside and find a new way to live.

She explores the labyrinths of a litany of recent TV and movies' geographies and geometries, describing how their occupants seek to get out, by any means. By extension, subliminally, we seek to escape our prison, our many deep entrapments. But she turns the mirror back on ourselves, like Walt Kelly: 'We have met the enemy, and it is us'. But she phrases it differently:

We’re not stuck in our circumstance. We’re stuck in the ways of living that perpetuate it.

If enough of us give up the sense that things are inevitable — that we’re stuck — it’s possible that we can course-correct humanity, or at least nudge it toward a hopeful path.

There’s another more realistic option that offers a thrill and reward of its own. If we don’t let the stucktopia keep its hold on us, if we rebuke it, maybe we shift ourselves ever so slightly toward optimism, and give the system whatever small hell we can.

Is Ghosting better than Love Bombing?

In Bad hiring practices are harming employer brands, shrinking talent pools, Hailey Mensik highlights another aspect of the social media backlash for bad HR experiences. Moving beyond dissing former employers on Glassdoor, job candidates are chronicling their misadventures in companies broken hiring processes:

Poor hiring practices are starting to bubble up for employers, and not in a good way.

A growing number of people are airing their grievances about badly conducted hiring experiences, which are a turn-off to other candidates, according to data from platforms like Glassdoor.

On Glassdoor and Indeed, job seekers who had poor hiring experiences are dropping “Yelp-like feedback,” about certain companies, giving written reviews and numbered ratings that can be hard to turn around, said Neil Costa, founder and CEO of HireClix, a recruitment marketing services company.

“If it’s a downward trend, it’s just like getting a C on your midterm. It’s hard to bring your average up over time,” Costa said.

Some of those poor practices include ghosting, or starting the interview process with candidates then cutting off all communication without an explanation. There’s also love bombing — where candidates are showered with praise only to be lowballed with a salary offer or title not aligned with their experience. Hard-to-navigate careers pages or hiring portals are another issue irking job seekers, along with lengthy take-home assignments.

Ex-employees have long turned to sites like Glassdoor to write scathing reviews about employers they feel mistreated by, having worked there for a period. That’s always been a red flag for job candidates who do their research thoroughly. But people are now writing bad reviews about how employers conduct interviews, which is equally damaging for an employer’s brand and could turn off others before they even apply, shrinking talent pools and hiring teams’ chances of finding the right person for a role, recruitment professionals say.

Judge them on their behavior, not their rhetoric.

Time Confetti

In Hybrid office tribes are here, and they’re a problem, Jack Needham digs into the potential for friction and hostility between work-from-homers and in-office staff.

Once, cliques were formed at desks, split between different departments and evidenced at Christmas parties and after work drinks. Now, the causes of cliques are a little more convoluted as staff are divided between the office and home, as well as those who only work certain days of the week.

“Work tribes aren’t a new thing,” says Amy Butterworth, a psychologist and principal consultant at Timewise, a workplace consultancy. “We tend to gravitate to those with similar lives and experiences to us.”

They are as old as work itself, but this is something different:

Another big challenge with cliques is that there is a danger of creating what Dr Nicola Millard, principal innovation partner at BT, calls a ‘two speed organisation’: a disjointed workforce who fail to collaborate. “To quote Frankie Goes to Hollywood, we know that two tribes can very easily go to war,” says Millard.

The office tribe, explains Millard, tends to operate to a fixed block of time of 9-5, copes with more friction – commuting, desk-based collaboration – and forges relationships face-to-face.

The remote tribe, meanwhile, works in a mode Millard describes as “time confetti”. They generally start earlier, finish later, work frictionlessly and take more breaks, but their social ties tend to be weaker because the majority have been formed online. “One casualty might be the office romance, but tribalism and distrust of ‘out groups’ can cause serious damage to people’s willingness and ability to collaborate with others,” says Millard. “This is why the ability to network – both in digital and physical space - is a skill that we all need in a hybrid workplace.”

We owe the term ‘time confetti’ to the wonderful Brigid Schulte, who collated research on the costs of fragmenting the workday into tiny slices, people like Leslie Perlow and her description of ‘time famine’ (See 24 Years Ago, a Harvard Researcher Showed How to Increase Productivity at Work by 65 Percent. Why Aren't We All Using Her Method? | Jessica Stillman). The answer is to give people larger chunks of unbroken time, and to move away from meetings to open asynchronous communications.

Remote first organisations tend to have a more open, written culture, says Butterworth, where the work can be seen and discussed by everyone at any time. Millard agrees. “The pandemic has shown us that digital is a great leveller,” she says. “When everyone is sitting in their own virtual celebrity video square, everyone is equally visible. This suggests that the hybrid office is digital first.”

Mired in The Ecosystem

Via Erik Hoel, we learn about Joshua Skagg’s attempt to free himself of Googledom:

Skagg: Trying Google alternatives is like swapping your steering wheel for a squishy joystick because it’s more “ergonomically correct,” which is fine until someone wants to borrow your car. You never realized how easy it was to rattle off your email address and close with “@gmail.com” until you have to spell out “P-R-O-T-O-N-mail” twice a week. You start to suspect that maybe you’re the idiot here.

Hoel: My sympathies on this one: I once wanted to migrate away from Apple products and basically realized at some point it was simply too complicated and I was stuck in the ecosystem until the day I die.

I spent some time looking at Google alternatives. But I judged them all by the degree I would have to relearn how to do basic things. So, no to Vivaldi browser, no to Proton mail, no to a long list of alternative calendars.

Factoids

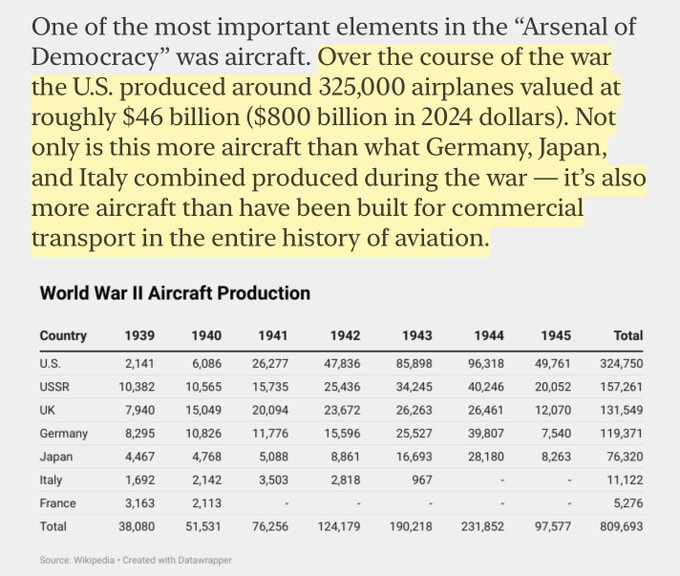

That’s a lot of planes.

Via Auren Hoffman:

We could be building more, like sufficient housing, and the economy would take off.

Elsewhere

Work cliques, redux.

Nine out of ten industry executives told McKinsey & Company earlier this year that their organisations will be combining remote and onsite working. However, 68 per cent of organisations have no detailed plan as to how they’ll actually do it.

| Jack Needham, Hybrid office tribes are here, and they’re a problem

…

Out-migration.

In Economics Daily, Rich Miller and Chris Anstey explore new research:

'Brandeis University economist Jiwon Choi found that towns walloped by plant closures actually tended to see less out-migration than others.' Negative evidence for training after layoffs or plant closings. Remember Janesville, Wisconsin and Lordstown Ohio.