On The Soil They Cultivate

Karl Marx | The Enclosure Of Work | Factoids

The last great process of expropriation of the agricultural population from the soil is, finally, the so-called ‘clearing of estates’, i.e., the sweeping of human beings off them. All the English methods hitherto considered culminated in ‘clearing’. As we saw in the description of modern conditions given in a previous chapter, when there are no more independent peasants to get rid of, the ‘clearing’ of cottages begins; so that the agricultural labourers no longer find on the soil they cultivate even the necessary space for their own housing.

| Karl Marx, Das Kapital

The Enclosure Of Work

In Das Kapital, Karl Marx makes a case for capitalism’s origin in the transition from ‘primitive communism’ — the sharing of natural resources by agrarian (and pre-agrarian) communities — and the emergence of land enclosure that incorporated “land into capital”.

As summarized by John Bellamy Foster, Brett Clark, and Hannah Holleman in Marx and the Commons [emphasis mine]:

In his famous section, “so-called primitive accumulation,” in volume one of Capital, Karl Marx argued that the enclosure of the commons and the expropriation of the land and lives of peoples throughout the world constituted the necessary preconditions for the agricultural and industrial revolutions in England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The genesis of modern capitalism was the result of a process of worldwide expropriation that is still occurring today. Capitalism is the negation of the commons, which, in turn, in the higher form of socialism, can be seen as the negation of capitalism (the negation of the negation).

Private property, as a form of appropriation, requires as its basis enclosure and exclusion. Public wealth or use value is subordinated to the promotion of private riches or exchange value. In contrast, common or communal property, even occurring within feudalism and other tributary modes of production, is associated with collective rights of production and appropriation within a given community while promoting use values or non-commodity forms of wealth. Whereas private property is alienable, since it takes a commodity form and serves as the basis of an exchange economy, traditional communal property in the land is not, as it is rooted in a combination of historical rights associated with meeting the needs of a particular community or locality.

The commons was more than just the shared, non-arable land on which commoners grazed cattle, cut wood and hay, and fished in lakes and streams. It was the long-established sharing of nature — tillable fields, woods and fields for hunting, and rights to glean after harvests — linked to station and habitations. Widows, for example, had specific rights, and cottagers might have the right to graze their pigs in the woods, having forfeited the right to hunt deer.

What was lost when landowners decided to ‘enclose the commons’ in favor of industrial farming was not just access to the formerly communally-worked ‘commons’, but the relations between the many participants, both landowners, commoners, and everyone else in the lands expropriated. The previous sense of mutual obligation — where the feudal landowners were obliged to support those living on the land through rights to the common, and commoners in turn agreed to the rights of those governing — was buried under in the transition to dispossession and a new form of servitude. In place of a feudal servitude linked to the land, those cut off from the commons became paid workers for the landowners, or moved to the factory towns, as laborers, forcibly displaced from their birthrights.

The uprising of so-called ‘Blacks’ — who concealed their identities by blackening their faces — challenging enclosure by poaching and other actions made illegal, led to the Black Act, which made it a capital crime for even thinking about defying the law. Robin Hood may have been a Black, although the term has fallen out of use.

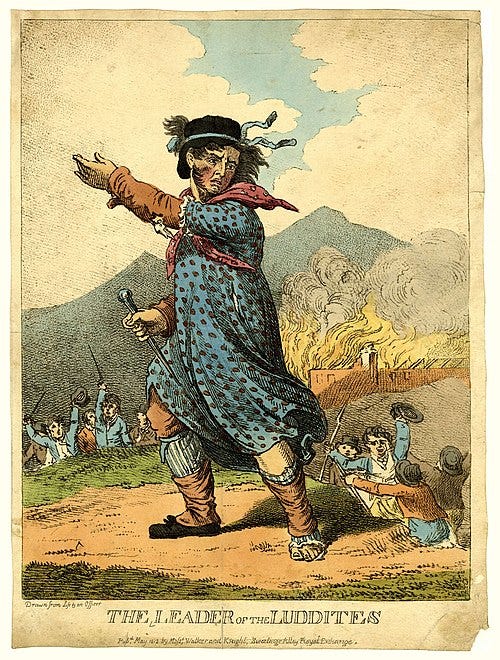

At the same time, industrialization commodified work, as in the famous example of highly skilled weavers who rebelled when automated looms enabled unskilled workers to take their place in the economy, driving down wages for all. The uprisings following that technological innovation were associated with the legendary Ned Ludd, from which the term Luddite is derived.

Enclosing the commons made peasants into laborers, industrialization made skilled laborers into task workers, and at each step, rebellion followed. As the seemingly inexorable march of technology further alienated workers from their ‘natural economies’ — their relations to each other and their work — we have seen the rise of trade unionism as a check on the excesses of capitalism. But — in the US, at least — trade unionism is in free fall, and the struggle of populations around the world in defense of greater equality and human development continues without a Ned Ludd.

Today, we are confronted by AI fever dreams, which amount to a neo-industrial enclosure of our inalienable rights. Amazon — America’s second-largest employer — announced that it plans to replace half a million workers with robots, and thousands of other companies no longer attempt to conceal similar goals for AI. We need to accept that their goal is to automate everything possible, pushing the AI-era ‘peasants’ out of the new enclosure: work itself.

Back in 2014, I was a member of a panel of experts selected by the Pew Research folks to answer some questions about the impact of AI and robots on work, looking ahead to 2025. Among other things, I wrote,

The central question of 2025 will be: What are people for in a world that does not need their labor, and where only a minority are needed to guide the ‘bot-based economy?

We are seeing again what Marx wrote about the English enclosures,

[A] whole series of thefts, outrages and popular misery that accompanied the forcible expropriation of the people.

Do we have the right to a job, and a way of life based on working for a living? In a world dominated by corporations and institutions that have broken with the neo-feudal compact between worker and employer, the final step is to displace us from work, itself.

Even with the precarity of today’s economy, with company leaders openly saying loyalty is dead, everyday people still believe in work, as in having a vocation and following it. But the growing trend in corporate boardrooms is to consider workers as dead weight to be jettisoned as soon as AI makes it possible. Just as the English gentry at the start of the industrial revolution saw the peasantry as only an impediment to industrial farming, leading to enclosure, displacement, and the clearing of the land, so too today’s corporate gentry seeks to enclose work itself, to displace all employees, and to clear the offices and factories, except for robots and AI, and a handful of owners and engineers to keep the machinery going.

Where is the Ned Ludd we need to raise the rebellion? Who will shout, ‘Smash the machines!’ Who will say, ‘Follow me!’

The AI overlords are not going to decelerate on their own: we will have to make them, before they completely enclose the commons of work.

Factoids

Nostalgia for a time before they were born.

Clay Routledge, in Gen Z-ers Are Nostalgic for a Time Before They Were Born:

80% of Gen Z adults — that is, those born after 1997 — were worried that their generation was too dependent on technology. 75% were concerned about social media’s impact on young people’s mental health, and 58% said that new technologies were more likely to drive people apart than bring them together. 60% of Gen Z adults said that they wished they could return to a time before everyone was “plugged in.”

…

US without immigration.

Immigration is a critical factor in US economics, Charter tells us:

Without immigration, the US population of working-age adults is expected to shrink by 3.2 million people by 2035, slowing GDP growth. Economists at the Economic Policy Institute estimate that the average annual GDP growth from 2026 to 2035 will be 1.47%, 0.36 percentage points lower than the Congressional Budget Office estimates of 1.83% for the same period.

The authors note that maintaining normal levels of GDP growth is impossible without immigration, even with significant productivity increases among the existing workforce. (They don’t directly address whether AI could reduce the demand for human labor.)

Even cutting current immigration levels by half would reduce average annual GDP growth by 0.2 percentage points annually due to low birth rates and an aging US population.

Economists note that drastic cuts to immigration will increase prices, reduce output, and dampen innovation and productivity in key sectors. They predict that increased immigration enforcement and new restrictions on H-1B workers will strain the labor supply in both low-wage sectors like construction and highly skilled functions such as AI and biotechnology.

Ending immigration is a terrible idea. They don’t quantify it, but today’s GDP is $30.5 trillion, so a 0.4% drop is on the order of $122 billion per year.

…

The more scientists work with AI, the less they trust it.

Joe Wilkins reports on scientists' skepticism of AI [emphasis mine]:

Scientists are a skeptical bunch — it’s in the job description. But when it comes to AI, researchers are growing increasingly mistrustful of the tech’s capabilities.

In a preview of its 2025 report on the impact of the tech on research, the academic publisher Wiley released preliminary findings on attitudes toward AI. One startling takeaway: the report found that scientists expressed less trust in AI than they did in 2024, when it was decidedly less advanced.

For example, in the 2024 iteration of the survey, 51 percent of scientists polled were worried about potential “hallucinations,” a widespread issue in which large language models (LLMs) present completely fabricated information as fact. That number was up to a whopping 64 percent in 2025, even as AI use among researchers surged from 45 to 62 percent.

Anxiety over security and privacy were up 11 percent from last year, while concerns over ethical AI and transparency also ticked up.

I have two degrees in science, so that may explain my skepticism.

…

Load-bearing?

Jennifer Mattson, in Meta AI layoffs today: 600 jobs are already being cut from Alexandr Wang’s superintelligence lab, revealed a new euphemism for me:

“By reducing the size of our team, fewer conversations will be required to make a decision, and each person will be more load-bearing and have more scope and impact,” Meta chief AI officer Alexandr Wang wrote in a memo, Axios reported.

More work because 600 former workers are now gone translates to ‘more load-bearing’ as if that’s a positive thing.

…

No more sandwiches.

Rachel Dry avoids the term 'shit sandwich' but that’s what she’s talking about:

It’s possible your boss went for the “compliment sandwich,” a feedback technique that, as you might guess, puts some flattering observation on either side of an unpleasant truth.

I attended a management training a few years ago where we were explicitly told, “Hey, no more sandwiches.” The idea being: People are most likely to remember the last thing they heard. So if it’s a compliment, that’s what they’ll leave the meeting thinking about. The critical feedback or notes on needed improvements will fade from memory and only the gold star will remain.

If that was the message to your colleague — “we need you, you’re amazing, you’re not getting the promotion, we really need your incredible contributions” — it could make it difficult to move on from the disappointment of not getting promoted, since it won’t make sense.

Avoid creating cognitive dissonance.