Quote of the Moment

Someone once said that all the great truths are basically trivial and so we have to find new ways, preferably paradoxical ways, of expressing them, in order to keep them from falling into oblivion.

| Jose Saramago, The Double

Economics: Why Do Wages Rise In A Down Economy?

In How Do Workers’ Wages Relate to Inflation?, Paul Krugman notes that although wages 'are just another price', they aren’t:

But employment is, in fact, a human relationship, and this makes a difference even in a market economy.

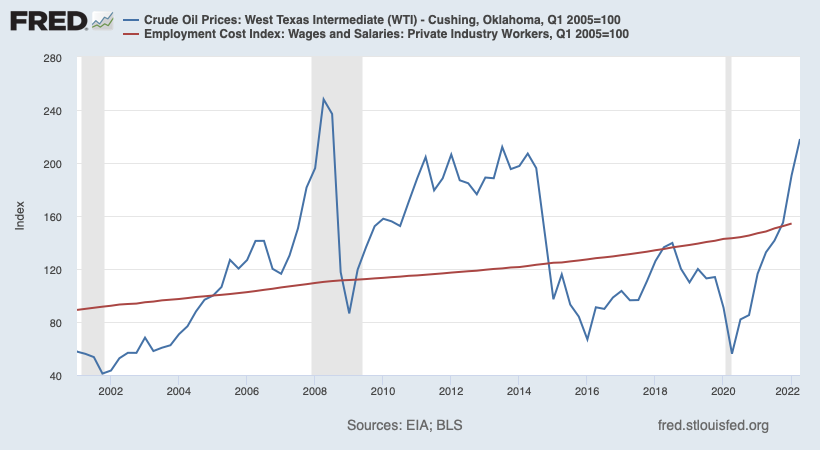

Over several periods of mass unemployment in recent years -- when companies fired employees despite those ‘human relationships’ that connect workers to their employers -- the paradox is that wages have steadily grown:

Does this confound the Marxist claim that in a market economy work is commodified? No.

Krugman cites the economist Truman Bewley, who wrote a book on the topic, Why Wages Don’t Fall During a Recession:

Unusually for an economist, he tried to answer the question by actually talking to people — specifically employers, who seemingly could have demanded givebacks from their workers during the 1990-91 recession and the long “jobless” recovery that followed. Why didn’t they take advantage of the opportunity?

The answer, he found, came down to the fact that workers aren’t barrels of oil or bushels of soybeans. They’re people, who, among other things, get upset when they feel taken advantage of. Nobody worries about the feelings of a barrel of oil; employers worried that cutting wages, even during an economic downturn, would hurt their employees’ morale and that the resulting damage would outweigh any cost savings.

But I think the shrewd calculations of employers (as Bewley learned in his investigations) do not in fact support the notion of some magical power of 'human relationships'. The reason employers don't cram wage cuts in downturns is just that workers would resent it, and would vent their frustrations by being less productive. Cramming down wages would cost more than would be saved.

So, the 'human relationship' is actually a commodification of work, after all. It's just that the workers won't act like barrels of oil, although their bosses would be happier if they would.

Work Talk: Quiet Quitting

A new term is surfacing, Quiet Quitting:

You’re not outright quitting your job, but you’re quitting the idea of going above and beyond. You’re still performing your duties, but you’re no longer subscribing to the hustle culture mentality that work has to be your life – the reality is, it’s not.

| @zkchillin, On Quiet Quitting

A new form of minimum viable work.

Ellen Scott writes about this in Could the quiet quitting trend be the answer to burnout? What you need to know.

What does quiet quitting look like in practice? It might be saying no to projects that aren’t part of your job description or you don’t fancy doing, leaving work on time, or refusing to answer emails and Slack messages outside of your working hours.

So, basically, living a life — like leaving work on time, and treating non-work time as actually time-to-not-work — is almost like quitting, now. Scott and various ‘experts’ position ‘quiet quitting’ as more like quitting than just a normal relationship to work. I think @zkchillin is closer to the mark in his assessment.

And Scott continues down the path of asserting that QQing is a sign you need to find a new job:

‘Quietly quitting is often a sign that it’s time to move on from your role,’ says Jill Cotton, career trends expert at Glassdoor. ‘If you’re reducing your effort to the bare minimum needed to complete tasks, your heart is probably no longer in the job or the company.

I guess that just doing your job and going home at the end of the day is unacceptable. The job is supposed to be primary, and you are secondary.

I am reminded of Jennifer Aniston’s Joanna in Office Space, who was hounded by her manager for wearing only the minimum ‘flair’ — buttons and other nominally personally-selected kitsch — on her uniform:

Another example of this ‘emotional labor’ — forced happiness, and the requirement for performative over-involvement and emotional availability— was Pret A Manger’s rules for store employees:

Details have emerged of a regime of 'enforced happiness' at Pret A Manger, where staff earning little more than the minimum wage are monitored to ensure they are relentlessly cheerful behind the counter.

The bizarre 'emotional labour' rules mean employees of the popular sandwich chain are expected to be 'charming', to 'have presence', and to 'care about other people's happiness', and should never be 'moody', or 'just here for the money'.

Mystery shoppers visit branches every week to ensure all staff are displaying 'Pret perfect' behaviour.

Pret perfect! The ideal employee 'cares about other people's happiness' and is not 'just here for the money', according to a list of Pret 'behaviours' that has been removed from the chain's website.

While 'friendly' and tactile employees who high-five colleagues as encouragement and 'create a sense of fun' would be welcomed by the chain, Pret does not want to see a team-member who doesn't interact with others or 'minces words'.

Yikes.

Wrapping It Up With A Bow

Maybe the rise of quiet quitting is exactly the sort of slowdown in productivity that a reduction in wages would lead to. While employers are not directly cutting wages, they are in effect doing so, because wages are not keeping up with the huge spike in inflation we’re experiencing.

Instead of lecturing quiet-quitters about reconnecting to their inner hustler, perhaps employers should pay them what their work is worth.

Economists like Paul Krugman might worry about the wage-price spiral, but I am a lowly, lowly newsletterer, and what I care about is people.