Short Takes #14: The Theft of the Future

Sarah Kendzior | US Unemployment | US Construction Deaths | Tech Spending Matches 2001 Peak | Hating On LLM Users

There is no satisfaction in being right about terrible things. That’s what many miss about the people who investigate conspiracies: in the end, we would rather be wrong. We would happily be mocked as hysterics and alarmists if it meant everyone could avoid the fate we foresee. When our theories involve the theft of the future, there is no benefit, not even financial, in scaring everyone senseless. This applies to my fellow realists labeled scaremongers: the climate scientists, the epidemiologists, the scholars of authoritarian states.

| Sarah Kendzior, They Knew: How a Culture of Conspiracy Keeps America Complacent

…

And we have to keep our eyes on the politicians, CEOs, and leaders of institutions, who are explicitly or implicitly supporting the theft of our future.

US Unemployment

In the US, it now averages more than 11 weeks to find a new job.

This might motivate the Fed to lower rates, although it seems unlikely that they will do so this week.1

Unemployed Americans are taking longer to find new jobs than at any point in the past four years as muted hiring deepens concerns about the labour market.

It now takes an average of more than 11 weeks for an unemployed person in the US to find a new job, the longest since 2021. Some 26 per cent of the 7.5mn unemployed actively searching for work have been looking for more than six months.

via Mohamed A. El-Erian, who writes:

This matters, especially at this economic/political/social juncture. Moreover, the longer the unemployment period, the higher the risk of [the unemployed] becoming a lot less employable.

A negative feedback loop.

US Construction Deaths

Construction workers have the highest rate of suicide in the US.

The construction industry has one of the highest suicide rates of any major industry in the country, second only to mining, according the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Add in drug overdoses, where construction workers die at a greater rate than workers in any other industry, and a bleak picture emerges of a population in crisis.

Construction is already among the most dangerous jobs in the country, with about 1,000 people dying each year from work-related injuries, more than any other industry. But five times as many workers, 5,100, died by suicide, and 15,900 died from drug overdoses, in 2023, according to an analysis of the most recent federal data by the Center for Construction Research and Training, an occupational safety organization. While the number of overdoses declined from 2022, from 17,000, the number of suicides remained virtually unchanged.[…]

No occupation has a higher rate of substance abuse than construction and extraction. A substance abuse disorder, even for someone in recovery, increases suicide risk.

| Ronda Kaysen and Sophie Park

A very difficult mess to unsnarl.

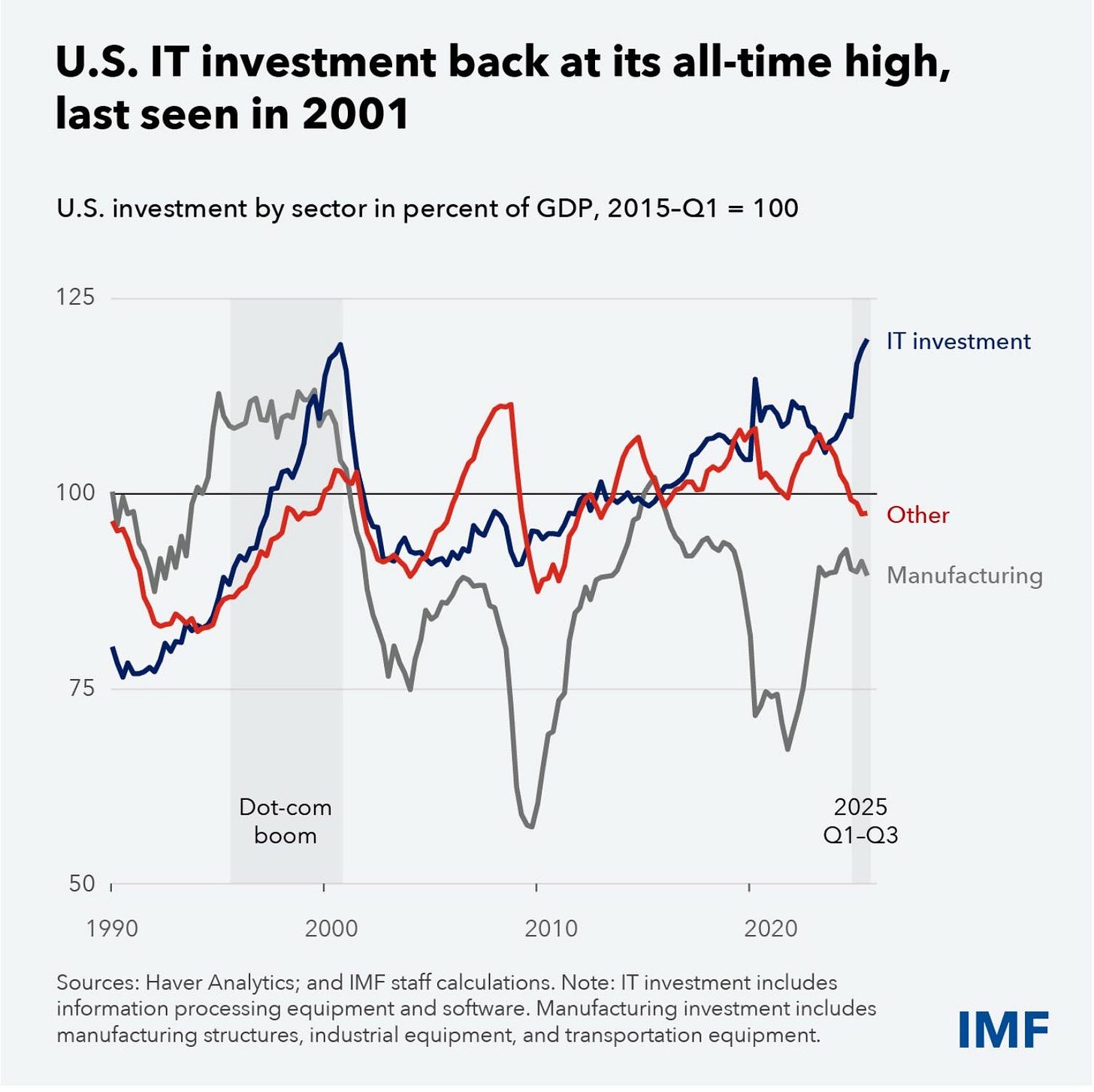

Tech Spending Matches 2001 Peak

Tech spending, as a percent of GDP, and largely driven by AI, is back to its 2001 all-time high. Remarkable.

It’s looking awfully bubblicious.

Note how wonderful Trump’s tariffs have been for manufacturing.

Hating On LLM Users

Antisocial behavior towards large language model users: experimental evidence | Paweł Niszczota, submitted on 14 Jan 2026 [emphasis mine]:

Abstract: The rapid spread of large language models (LLMs) has raised concerns about the social reactions they provoke. Prior research documents negative attitudes toward AI users, but it remains unclear whether such disapproval translates into costly action. We address this question in a two-phase online experiment (N = 491 Phase II participants; Phase I provided targets) where participants could spend part of their own endowment to reduce the earnings of peers who had previously completed a real-effort task with or without LLM support. On average, participants destroyed 36% of the earnings of those who relied exclusively on the model, with punishment increasing monotonically with actual LLM use. Disclosure about LLM use created a credibility gap: self-reported null use was punished more harshly than actual null use, suggesting that declarations of “no use” are treated with suspicion. Conversely, at high levels of use, actual reliance on the model was punished more strongly than self-reported reliance. Taken together, these findings provide the first behavioral evidence that the efficiency gains of LLMs come at the cost of social sanctions.

The taint of LLM use leads — in experimental conditions — to participants ‘punishing’ those who use LLMs, or are suspected for lying about such use.