Terrifying People

Ian McEwan | Factoids | Elsewhere and Elsewhen

As I get older, I begin to feel that actually what we need more in the world is doubt; more skepticism, less crazed certainty... People who know the answer and are going to impose it on everybody else, I think, are terrifying people.

| Ian McEwan

…

I am working on a number of larger posts, but they are delayed. Here’s a smorgasbord of smaller bits.

Factoids

Climate.

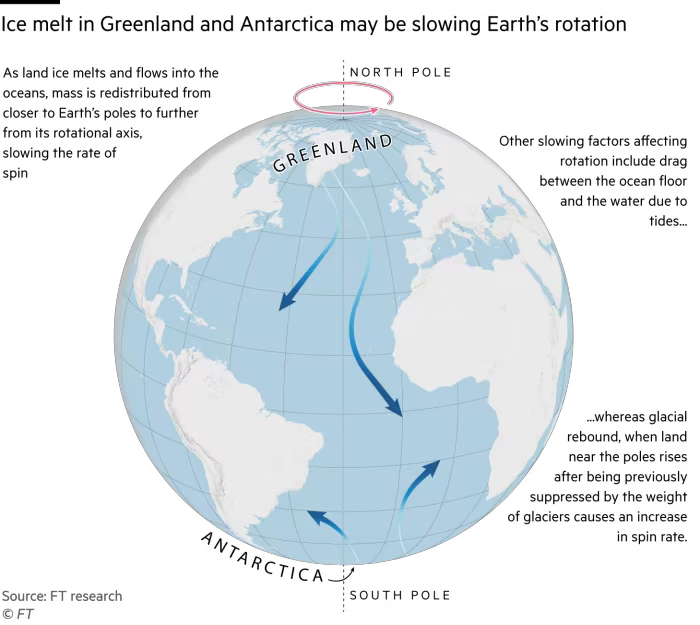

Climate change is causing so much polar ice melt that it's slowing down Earth's rotation and — here's the kicker — it will alter how we measure time in the future.

Angular momentum is a bitch. Also, the moon is slowly moving away from the earth, too, so the tides will lessen.

…

By 2050, global demand for electricity is expected to rise by as much as 75 percent.

| U.S. Energy Information Administration

…

in 2023, nearly 86 percent of the new power generation built worldwide came from clean sources.

| International Renewable Energy Agency

…

It’s better to be an owner.

67% of owner-employers are thriving in wellbeing, compared to 52% of non-employer owners, 51% of employees and 48% of self-employed workers.

| Gallup

Owner-employers are way happier. And living way way more comfortably.

…

Homelessness is worsening.

The U.S. is likely to top the roughly 653,000 homeless people estimated in 2023—the highest number since the government started reporting comparable data in 2007.

| Jon Camp

Elsewhere

Real wages for non-managerial workers are up. Way up.

Between 2000 and 2017, real wages for non-managerial workers grew slowly, with little deviation from a relatively flat trajectory. However, from 2017 onward, as the labor market tightened, wage growth for this group became much stronger. Despite the disruptions caused by the pandemic and the burst of inflation in 2021-2023, real wage levels remain well above pre-2017 trends. The fact that real wages have continued to rise, even in the face of inflation, is a testament to the power of full employment in driving wage gains.

| Arin Dube, Real Wage Growth: The Post-Pandemic Labor Market and Beyond

Note that the trendline is based on 2000-2007 extrapolation. Average non-managerial wages have moved on to a new, higher trendline. Of course, the cost of goods and services are are up, too, but their rise is slowing.

…

Is this how to predict the future of work?

In What 570 Experts Predict the Future of Work Will Look Like, Nicky Dries, Joost Luyckx, and Philip Rogiers use three perspectives teased out of personality tests -- optimist, skeptic, and pessimist -- as three scenarios of how people think about the future of work. Note that they only survey deeply engaged people -- 'experts' -- not the average worker who I guess don't think about the future of work, or the authors think they will get better material from experts.

I wondered about studies that use political or philosophical orientations: would they show different results? Do conservatives think differently about the future of work than progressives?

Some fragments:

'We can’t predict the future of work, but we can predict your prediction.'

…

'The question is thus not, “What will the future of work be like?” but rather, “What do we want the future to be like?” This reframes the future-of-work question as an arena for values, politics, ideology, and imagination, instead of a set of trends that can objectively be predicted.'

Ok, but that reminds me of ‘you promised flying cars and all we got was 140 characters’. The problem is that the personality types do not average out to a coherent vision about the future of work. All you get is a blur, a Frankenstein’s monster from three non-overlapping visions.

But if some group has an agenda -- for example, a strong motivation to decrease CO2 emissions -- then they will want the future of work to minimize commuting, and therefore they would take a principled stand against the return-to-office reationaries. By retreating to a free-floating judgementless stance, the authors apparent neutrality is triangulating between the three perspectives, a sort of ‘view-from-nowhere’.

Their three-part recommendations are typical consultant speak. All they are doing is turning down the volume: it's the same old song:

So, what can you start doing today? First, from now on, whenever you hear or read something about the future of work, don’t just look at what is predicted (and by when), but also who is saying it and why. What vested interests do they have? What society do they want, and how does it benefit them? Second, what is your utopia for the future, and what is your dystopia? What should we do — or stop doing — in the short-, mid-, and long-term to move towards your desirable scenarios, and to reduce the risk of undesirable ones? What can we do to avoid points of no return for the distant future, for instance, when we are thinking about the climate or superintelligent AI? And third, what do you have most control over from your position of power and influence in society? What forms of power and influence do you not have? Can you partner with others who have sources of influence complementary to yours, and who share the same utopia?

Good questions, but they go unanswered.

They only offer a way to distance ourselves from the hard work of how our imagined work utopias (or dystopias) interact with the larger context of politics, economics, and the natural world.

Work is a wicked problem because the larger world cannot be neatly factored into smaller systems: you can't change work without changing everything, and vice versa.

Elsewhen

Weak Ties And revolutions (With A Little 'R') | Stowe Boyd 27 September 2010:

Malcolm Gladwell wants to pop the bubble surround social media's supposed role in capital 'R' Revolutions, as in the #iranelections.

I think the real story is in lower case 'r' revolutions, but here's his core thesis:

Malcolm Gladwell, Twitter, Facebook, and social activism

The world, we are told, is in the midst of a revolution. The new tools of social media have reinvented social activism. With Facebook and Twitter and the like, the traditional relationship between political authority and popular will has been upended, making it easier for the powerless to collaborate, coördinate, and give voice to their concerns.

He was wrong then, and still wrong, today.