The Illusion of Truth

FDR | Illusory Truth Effect | Factoids | Elsewhere: OK meetings are not OK. | Elsewhen: Untangling Decision Making

Repetition does not transform a lie into a truth.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

However, the illusory truth effect means that people tend to believe ‘repeated information rather than novel information’. So, while repeating a lie doesn’t make it true, it does create the illusion of truth. In the next section, I explore how to counter that tendency.

The Illusory Truth Effect

As FDR tells us in the quote above, simply repeating lies doesn’t make them true. But a great deal of research converges on the opposite end of the story, which is that people are more likely to believe repeated information — even if untrue — than novel information, true or not.

In The Cognitive Shortcut That Clouds Decision-Making, cognitive scientists Jonas De Keersmaecker, Katharina Schmid, Nadia Brashier, and Christian Unkelbach lay out the basis for this cognitive bias and explore its ramifications in the workplace:

We live in a time of unprecedented access to information that’s available anytime and anywhere. Even when we don’t actively seek out opinions, reviews, and social media posts, we are constantly subjected to them. Simply processing all of this information is difficult enough, but there’s another, more serious problem: Not all of it is accurate, and some is outright false. Even more worrying is that when inaccurate or wrong information is repeated, an illusion of truth occurs: People believe repeated information to be true — even when it is not.

Misinformation and disinformation are hardly new. They arguably have been impairing decision-making for as long as organizations have existed. However, managers today contend with incorrect and unreliable information at an unparalleled scale. The problem is particularly acute for Big Tech companies like Facebook, Google, and Twitter because of the broad societal effects of misinformation on the platforms. A recent study of the most-viewed YouTube videos on the COVID-19 pandemic found that 19 out of 69 contained nonfactual information, and the videos that included misinformation had been viewed more than 62 million times.

In the world of corporate decision-making, the proliferation of misinformation hurts organizations in many ways, including public-relations spin, fake reviews, employee “bullshitting,” and rumormongering among current and future employees. Executives can find themselves on the receiving end of falsified data, facts, and figures — information too flawed to base critical decisions upon. Misinformation, regardless of whether it was mistakenly passed along or shared with ill intent, obstructs good decision-making.

A quibble: spreading untrue information with ill intent defines disinformation, actually, not misinformation, but it is generally difficult to know what people’s motivations are behind posting something on YouTube.

How does it work?

Psychologists refer to this phenomenon as the repetition-based truth effect or, in short, the illusory truth effect. Information we hear again and again acquires a “stickiness” that affects our judgment, and the effects are neither fleeting nor shallow. The illusory truth effect is in fact extremely robust, and its power has been shown repeatedly across a range of domains, from political speeches to product claims. One unsettling finding is that people fall prey to the effect not only when the original information is still fresh in their memories but also months after exposure. In addition, people judge repeated information as truer even when they cannot recall having previously encountered the information.

And all too often the advice of experts doesn’t counter the effect:

Enlisting a trusted expert to counter false information doesn’t help either; studies show that people believe repeated misinformation even when a reliable source argues that the information is incorrect.

In a rapidly changing world, we may not have the time to validate the ‘facts’ being considered as relevant to a problem, as the authors say, ‘especially in situations with some degree of uncertainty’. And nearly every decision involves uncertainty, these days.

Here’s an example laid out by the researchers:

A manager looking to hire a new member of the sales team has short-listed two candidates with comparable profiles, Jane and Susan, and interviews are scheduled for Friday.

On Monday, a team member remarks that Jane is very knowledgeable about the company’s product lines. This is new information, and the manager’s mind makes a connection between the candidate “Jane” and the concept “knowledgeable.”

On Wednesday, the same team member again mentions that Jane is knowledgeable about the company’s products, reinforcing the existing connection between “Jane” and “knowledgeable.”

On Friday, both Jane and Susan say they know a lot about the company’s products. Because the information about Susan is new and the information about Jane is not, the connection between “Susan” and the concept “knowledgeable” is not as strong as the connection between “Jane” and “knowledgeable.” And because the repeated information about Jane feels more familiar than the new information about Susan, the manager processes it more easily. This ease with which we digest repeated information is termed processing fluency, and we use this as evidence of truth. The manager is more likely to hire Jane.

How to counter this tendency in the workplace? First, remember that the illusory truth effect just happens, effortlessly, because as humans it is part of our repertoire of cognitive behaviors to learn about the world. We have to actively and intentionally work to counter it in decision making.

The authors offer four strategies:

Strategy 1: Avoid the bias blind spot. — Decision makers, even those with superior analytic skills or high intelligence, as as likely as others to fall prey to the effect. One reason is the bias blind spot, when someone thinks others are subject to biases but that they are not. This is a form of overconfidence, which cognitive behaviorist Daniel Kahneman and admitting you are subject to bias is the first step in overcoming it.

Strategy 2: Avoid epistemic bubbles. — A team dedicated to solving some problem can too easily form an epistemic bubble, where its members all share the same opinions and lack diversity of views. The authors point out ‘teams reflecting diverse perspectives outperform more homogeneous groups even when the latter have members with higher individual abilities on average’. Always keep in mind that the most novel and least repeated observations in a team discussion should be considered as valid as opinions widely shared and widely repeated.

Strategy 3: Question facts and assumptions. — ‘An accuracy mindset can help short-circuit the illusory truth effect with an emphasis on evaluating whether information fits with one’s knowledge, and it can promote a culture in which the default is to consider the truthfulness of new information when it arises.’ But the researchers go on to point out that few people critically evaluate information when presented to them. At the very least, ask yourself and others if the information is in fact true, which will hamper the illusory truth effect. Teach colleagues about the effect, and routinely question whether supposed ‘facts’ are true or not. And the researchers suggest ‘managers can ask team members to justify their decisions and to provide details about the information on which they’re based’. To which I’d add, all team members should be able to ask for such justifications. And teams should consider external fact checking when they are inexpert in some realm that impacts the decision. And this is probably only a recourse when stakes are high, not for every decision, because of the time involved.

Strategy 4: Nudge the truth. — Countering bad information by repeating good information works, but it’s important that you know the information is good. It also works best when an argument is repeated verbatim — exactly the same way each time.

Businesses and individuals should pay close attention to these recommendations. Repeating uncertain claims gives them undue weight, and undermines decision making’s deductive premise: we need to bring true facts to the table when making decisions, and the higher the stakes the more we need to do to confirm their truthfulness.

And we must look to ourselves first: don’t fall into the black hole of the bias spot: you are as likely to succumb to the illusory truth effect as anyone.

Factoids

Fear of dentists.

Studies of U.S. adults generally find that around 20 percent of respondents have moderate to high fear of dental care.

…

Not so hot.

The average human temperature is 97.9 degrees, not 98.6 as Carl Wunderlich reported over 150 years ago.

…

What makes women clean?

Women spend more than twice as much time allocated to household work than men, even when they are single or do not have children. And getting married doesn’t split the load for women, as it theoretically would, but increases it: married women without children still do 2.3 times as much housework labor as their husbands.

| Anne Helen Petersen, What Makes Women Clean [emphasis mine]

And later,

If feminism is, at least in part, the radical idea that women are people, then part of letting go of clean culture is the radical idea that women — and not just white, bourgeois women — deserve free time. More specifically: free time unburdened by the feeling that they “should” be cleaning or parenting or meal-prepping or doing laundry instead.

…

A post-truth world?

A study of the most-viewed YouTube videos on the COVID-19 pandemic found that 19 out of 69 contained nonfactual information, and the videos that included misinformation had been viewed more than 62 million times.

| Jonas De keersmaecker, et al, The Cognitive Shortcut That Clouds Decision-Making (2022) - see The Illusory Truth Effect, above, for more.

Elsewhere

OK meetings are not OK.

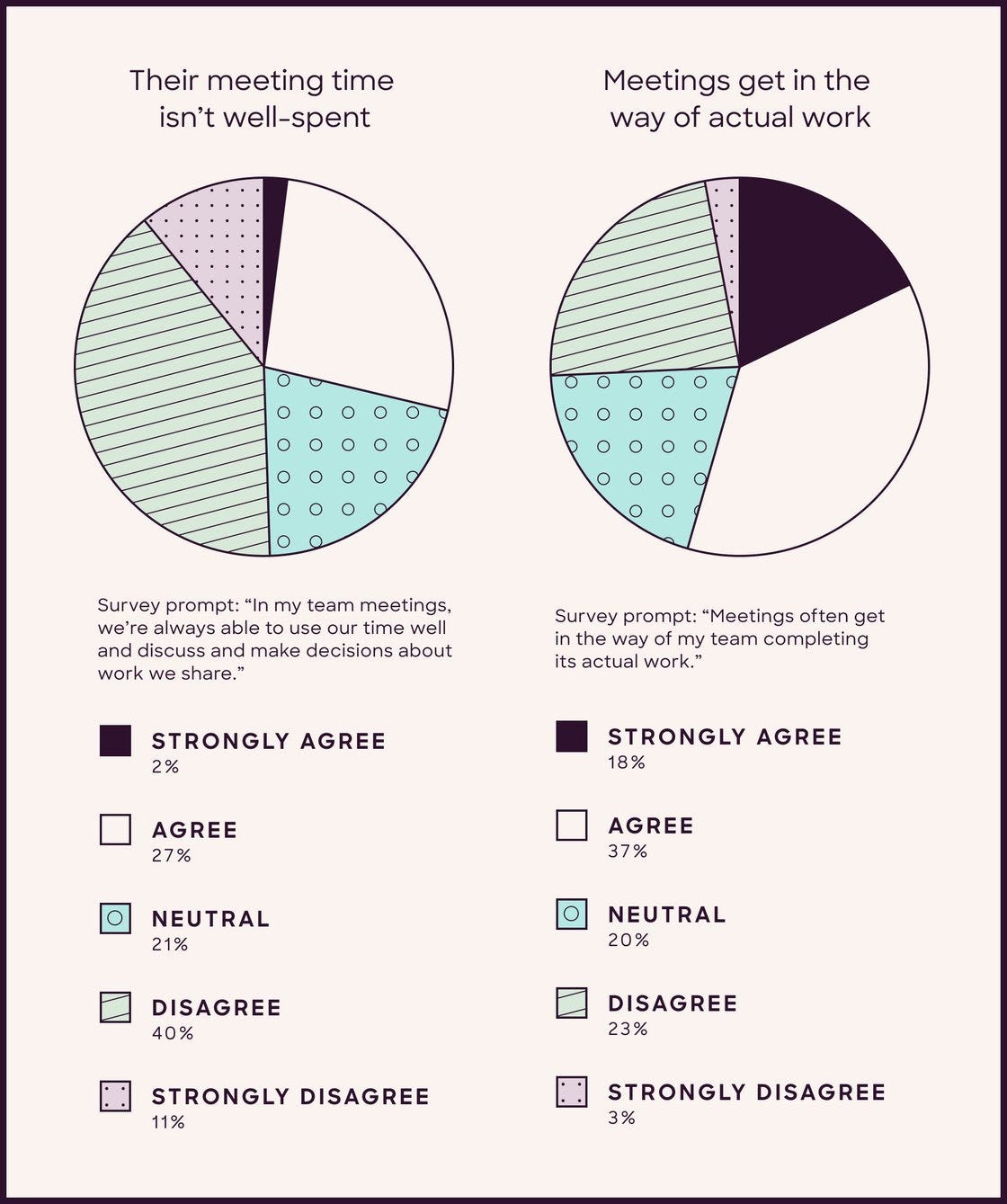

The Ready, a future-of-work consultancy, determined in a recent survey that 29% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed their meeting time isn’t well spent. Perhaps more important: 55% agreed or strongly agreed meetings get in the way of actual work.

The truth is meetings can be Band-Aids for all sorts of problems.

They paper over other issues or incoherence that demand a different quality of attention. When your organization struggles to use asynchronous tools to share and do work, enter more meetings. When leaders flex their authority by controlling the floodgates of information, enter more meetings. When your strategy hasn’t resulted in explicitly prioritized work, enter more meetings. Now, you’re trapped in a cycle of meetings breeding more meetings meant to solve problems that were caused by past meetings.

The two statistics above from our recent meetings survey represent a fork in the road. Organizations can either live with an overload of meetings that leave employees tired, spending inordinate amounts of time on inane things, and perhaps more confused than before. Or organizations can treat meetings like the powerful lever for problem-solving and decision-making they are—if designed in the right way.

It’s easy to overlook meetings as a habit worth strengthening. They’re not the sexiest of topics. And so many are garbage—so they stink up good meetings with the reputation of all the bad ones we’ve sat through. But we shouldn’t be OK with OK meetings, because there’s a throughline between doing a small thing well over time and vastly improving your entire operating system. If meetings are often a container for bad and ineffective behavior, then they could just as easily turn into a reliable space for an organization’s best behavior, ideas, delivery, and action.

| The Ready (email newsletter)

Elsewhen

Untangling decision making.

In September of 2019 I responded to some research on decision making, Untangling your organization’s decision making by Aaron De Smet, Gerald Lackey, and Leigh M. Weiss:

[The authors] share findings about decision making in organizations, starting with this telling stat:

72 percent of senior-executive respondents to a McKinsey survey said they thought bad strategic decisions either were about as frequent as good ones or were the prevailing norm in their organization.

While there is growing data, and an increasing awareness about cognitive biases that impede rational thought, nonetheless the growing complexity of organizations stands in the way of accountability.

This result is closely related to another finding: both high-quality decisions and quick ones are much more common at organizations with fewer reporting layers

[…]

The ultimate solution for many organizations looking to untangle their decision making is to become flatter and more agile, with decision authority and accountability going hand in hand. High-flying technology companies such as Google and Spotify are frequently the poster children for this approach, but it has also been adapted by more traditional ones such as ING (for more, see our recent McKinsey Quarterly interview “ING’s agile transformation”). As we’ve described elsewhere, agile organization models get decision making into the right hands, are faster in reacting to (or anticipating) shifts in the business environment, and often become magnets for top talent, who prefer working at companies with fewer layers of management and greater empowerment.

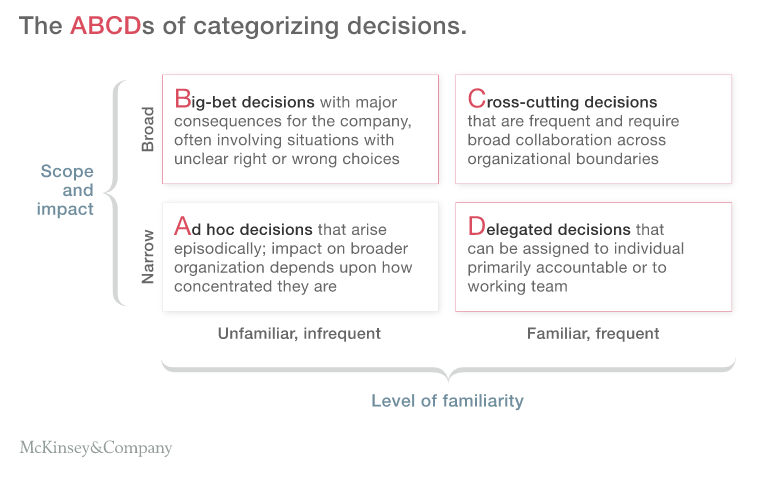

As we’ve worked with organizations seeking to become more agile, we’ve found that it’s possible to accelerate the improvement of decision making through the simple steps of categorizing the type of decision that’s being made and tailoring your approach accordingly. In our work, we’ve observed four types of decisions:

The authors dedicate the article to big-bet, cross-cutting, and delegated decisions. I find their approach very pragmatic, as this excerpt regarding bet-the-company decisions shows:

Appoint an executive sponsor. Each initiative should have a sponsor, who will work with a project lead to frame the important decisions for senior leaders to weigh in on—starting with a clear, one-sentence problem statement.

Break things down, and connect them up. Large, complex decisions often have multiple parts; you should explicitly break them down into bite-size chunks, with decision meetings at each stage. Big bets also frequently have interdependencies with other decisions. To avoid unintended consequences, step back to connect the dots.

Go read the whole thing.