They Should Not Pay

Claudia Sahm | Low Quality Jobs | Sad Desk Lunch | Stop Hiring Humans

Workers did not cause inflation, and they should not pay for bringing it down.

| Claudia Sahm, via Twitter

…

I thought of this Sahm tweet this week, following the interest rate decrease that the Fed announced, down another 25 basis points. Somehow, though, workers have paid and paid for the inflation we’ve seen in recent years.

Low Quality Jobs

The Upjohn Institute has released the first American Job Quality Study (AJQS), surveying over 18,000 Americans, and the first takeaway is only 40% report having quality jobs:

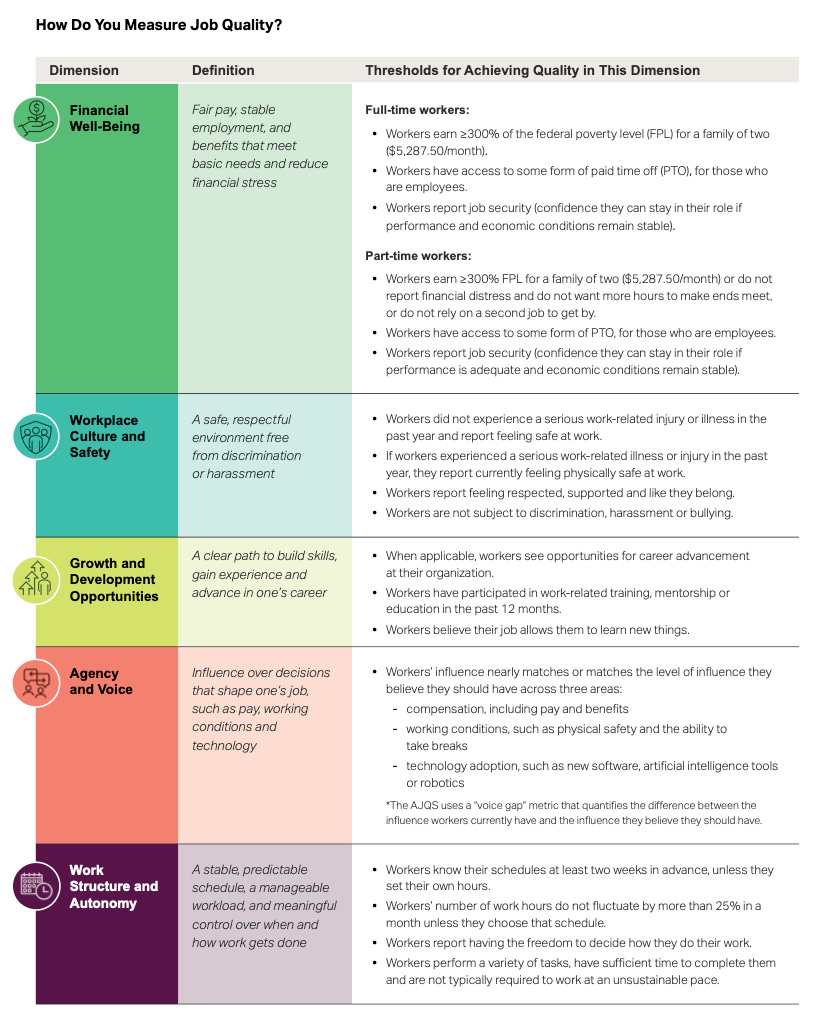

The first report on the AJQS, released today, offers an initial look at how many U.S. employees have quality jobs and who holds them. The study defines a “quality job” as one that achieves minimum thresholds across at least three of the five dimensions that research shows matter most to workers: financial well-being, workplace culture and safety, growth and development opportunities, agency and voice, and work structure and autonomy.

So, if American employers actually wanted to create quality jobs they are getting an F.

Here’s some more detail, which shows how low the floor is:

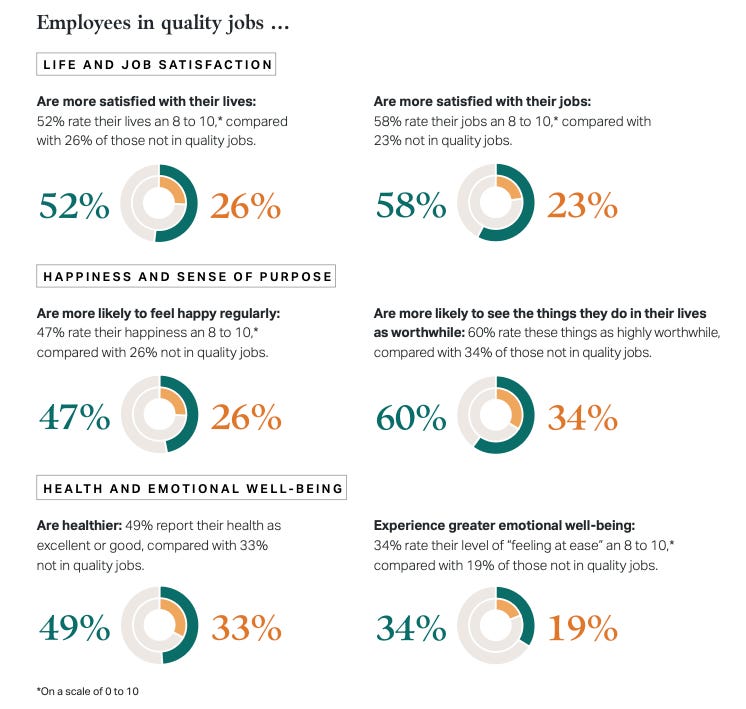

And employers should care, because workers with high quality jobs perform better:

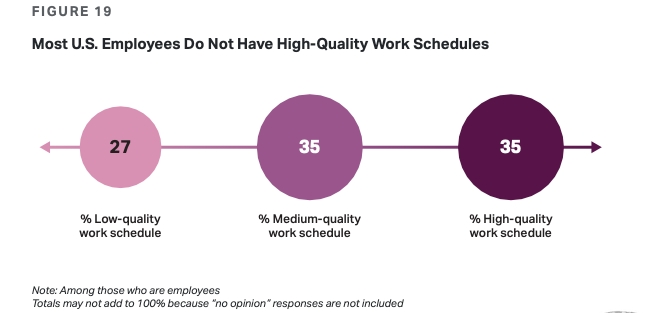

I’d like to zoom in on work schedules, because for hourly workers in particular, having unpredictable schedules can lead to major disruptions and costs. Only 35% report having a high-quality work schedule, meaning one where they have some control over it, and it is predictable or stable.

As Kathryn Anne Edwards reports on the study [emphasis mine]:

Longitudinal studies of family income in the 2000s and 2010s show volatile income and earnings pushed income above and below poverty levels. A study of annual incomes between 2007 and 2018 finds that 40% of households spent at least one year out of 10 in poverty. A study of monthly income between 2013 and 2017 finds that, in any four-year period, a third of Americans would experience at least two months in poverty.

Then came the seminal US Financial Diaries Project, published in 2017. A daily accounting of income and spending in low- and moderate-income households, it revealed not only the extent of income volatility, but how much of it was attributable to work. If the lesson 40 years earlier was that poverty came from disruptions to work that caused a drop in income, the diaries made clear that work, undisrupted, can cause drops in income. Individuals were steadily employed, but because of erratic schedules or the nature of their contracts, their earnings fluctuated wildly — even in the same job.

And they didn’t like it. When participants in the study were asked whether “financial stability” or “moving up the income ladder” was more important, 77% chose stability. Let me say that again: The vast majority of people would rather have predictable income than more income.

Depending on their status and education level, one-fifth to one-third of US workers have no control over their schedules.

In the past few years, researchers have studied the source and extent of unstable earnings. A key source of instability is work schedules: a growing share of workers do not get even a week’s notice about when or how much they will work. Another source is the “ gig-ification ” of wages, where being paid for time is replaced with being paid for service. This exposes the worker, instead of the employer, to fluctuations in customer demand.

The consensus among economists today is that the majority of workers in the US have income that changes month-to-month in an unpredictable way. So the American Job Quality Study is both unsurprising and significant. Almost every study of instability shows that it is more likely and more pernicious for lower-income workers, and that it creates financial stress and hardship, including episodic poverty.

Here’s an idea for the politicians: want to get elected? Rally supporters around the fundamentals of high quality jobs. Pass laws that, for example, require work schedules to be high quality. Yes, the employers will claim it will be costly. But they will get the benefits of lower turnover and higher productivity.

This could become a grassroots economic movement. Perhaps sensible Democrats will wave this flag, since it is something that should appeal especially to working class voters. And it has the benefit of being morally sound, and directly taking the fight to massive corporations like Walmart, Amazon, and Macdonald’s.

Sad Desk Lunch

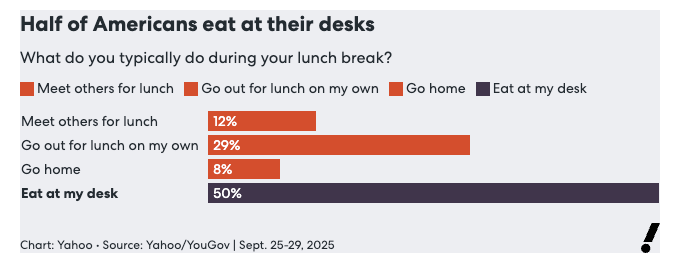

In our time-compressed work lives, it should come as no surprise that half of working Americans eat at their desks, according to Natalie Rahhal:

According to our polling, three-quarters of Americans who are employed by someone else do get a lunch break. About half of those people have paid lunch breaks, while half take lunch unpaid. In either case, the most common way that they spend their break is eating at their desk (50%). Just shy of 30% of workers go out for lunch on their own.

During lunchtime, nearly half (44%) just eat, taking a break from screens and tasks to focus on their food. But 38% spend this time scrolling on their phones.

Only 12% of respondents to our poll said they go out to lunch with others during the week. And, in reality, social lunches away from the office were only the cultural norm for a brief period and for a relatively small share of workers, Megan Elias, a professor of food and cultural history at Boston University and author of Lunch, tells Yahoo.

The modern lunch is really a product of the industrial revolution. Factories became the largest employers in the U.S. beginning in the late 19th century and peaking in 1979. Since then, “we’ve internalized what industrialization created, which is this timed day: The bell rings for morning, for lunch, for when it’s time to come back from lunch and when the day is over,” says Elias.

And of course of those eating at their sad, sad desks 38% are doom-scrolling.

Stop Hiring Humans

Artisan ad campaign: stop hiring humans. Question: is that woman’s likeness the AI employee or the person not being hired? Or the head of sales who is considering using Artisan’s sales workflow software?

The CEO of Artisan, Jaspar Carmichael-Jack, went on Reddit to deal with the backlash:

I’m CEO of Artisan, the company behind the “Stop Hiring Humans” billboards.

The campaign has gone way more viral than we ever expected - here to answer any questions people have :)

Boy, did they light into him.

Chris Blackhurst asks some questions about the campaign and the context [emphasis mine]:

It certainly hit a nerve. The slogans went viral, and opprobrium duly rained down. The US politician Bernie Sanders made a good point when he said, if we are going to be replaced by robots, who the hell is going to buy all the products that capitalism relies on selling to us? If the jobs market collapses, does capitalism?

Nice try, Bernie. If capitalism is about to die, the tech bros and their monied pals are not bothered. They are continuing to pour billions into developing AI, regardless. In the last quarter alone, an estimated $80bn (£61bn) has been invested in advancing AI.

It bears repetition: $80bn in three months. For no discernible payback. Not yet. It’s a bubble; of course it is. At any moment, this crazy headlong rush will crash, and then mayhem and global economic depression will ensue. But wait. These are not stupid people. They are making a bet, and their calculation has to be that human capital is to be substituted by something far cheaper and more efficient, and then the rewards will truly flow and those returns will dwarf anything they have put in.

Except that a great deal of financial analysis says that no, there can’t be a cataclysmic ROI for the hundreds of billions, if not trillions, being burned in the AI potlatch. Matteo Wong and Charlie Warzel tried to figure this all out, asking what if it’s all just shadow play?