True North

Lithuanian Skeletor | Conscious Unbossing | Seasonality: Finding Meaning and Purpose | Factoids

0nce you know your true north, everything else is logistics.

Join over 3,500 other Work Future subscribers (and over 5,000 followers) and sign up to these posts arriving in your inbox or the Substack app. Go on! You know you want to. Even better, sign up for a paid subscription to gain access to hundreds of posts behind the paywall on thousands of topics.

Conscious Unbossing

Last September, the recruitment agency Robert Walters conducted a survey through which they discovered a new trend:

72% of [UK] Gen-Z would actually opt for an individual route to advance their career – one which focuses on personal growth and skills accumulation over taking on a management role (28%).

Dan Pontefract interviewed Lucy Bisset, Director of Robert Walters North, who said,

It's not that Gen Z doesn't respect leadership, it's that they associate management with stress, limited autonomy, and poor work-life balance.

Or, said in a different way, they have had experience with leaders who project stress, limited autonomy, and poor-life balance, and they believe those factors are inherent in management.

No surprise, the survey also revealed that 52% don’t want to take on a management role. Hence, a new term of art, Conscious Unbossing, which represents this rejection of the management ladder as the obvious and most attractive path to professional growth and success.

Unbossing and Flattening

In the same survey, Robert Walter discovered other currents:

89% of employers still think that middle managers play a crucial role in their organisation.

So, Conscious Unbossing is not about bosslessness (which I’ve written about a number of times: It’s Bosses All The Way Down, and Making The Case For Hierarchy are just two examples), but being unwilling to assume the role of a boss.

But, Pontefract points out the view from Gen Z is quite different than the senior managers answering that survey question:

Gen Z's preference for flat structures and expertise-driven leadership suggests that companies might rethink their overall management structure. It might involve moving away from rigid vertical hierarchies and embracing a more collaborative, distributed form of leadership where decision-making and leadership are shared.

Pontefract and Bisset focus on a critical distinction: the Gen Z folks are motivated to acquire expertise rather than authority:

According to Bisset, the answer lies in creating alternate routes to leadership that focus on expertise, not hierarchy. "Younger professionals are seeking to become thought leaders and specialists," she says. "They're more interested in building their personal brand, developing niche expertise, and contributing to meaningful projects."

What is management like, five years or so in the future, when companies have trimmed middle management roles and Gen Z and even younger cohorts have sidestepped becoming bosses? Is this a fad, or an enduring change?

I’ll put a reminder in my journal to revisit this in a year, and we’ll see.

Seasonality: Finding Meaning and Purpose

I had thought about writing a short piece about applying Stewart Brand’s Pace Layers Model to our personal seasonality. After some reflection, I’ve decided it’s a bad match.

As I wrote a few years ago,

The brilliant Stewart Brand, along with musician and polymath Brian Eno, explored a model — the Pace Layers of Work — in which various elements of civilization are arrayed from fastest to slowest.

As Brand’s original caption reads,

The order of a healthy civilization. The fast layers innovate; the slow layers stabilize. The whole combines learning with continuity.

He goes on in his description

In a durable society, each level is allowed to operate at its own pace, safely sustained by the slower levels below and kept invigorated by the livelier levels above. "Every form of civilization is a wise equilibrium between firm substructure and soaring liberty," wrote the historian Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy. Each layer must respect the different pace of the others. If commerce, for example, is allowed by governance and culture to push nature at a commercial pace, then all-supporting natural forests, fisheries, and aquifers will be lost. If governance is changed suddenly instead of gradually, you get the catastrophic French and Russian revolutions. In the Soviet Union, governance tried to ignore the constraints of culture and nature while forcing a five-year-plan infrastructure pace on commerce and art. Thus cutting itself off from both support and innovation, it was doomed.

So the various layers have their own pace, fast at the top, slow at the bottom. Along with pace, they have differential levels of power and inertia.

I have made the comparison between Brand’s use of pace layers to model civilizational change and the changes within organizations (see A Working Equilibrium: The Pace Layers Of Work), but when considering the ebbs and flows of the individual, I could not see the two linking up well, perhaps because people aren’t layered in a simple way.

That led me back to a model centered on human development, the Ikigai-inspired Meaning/Purpose system I wrote about here, in 2023: Ikigai, Revisited. Looking back, the cycles that we can discern in human development are there for those with eyes to see them.

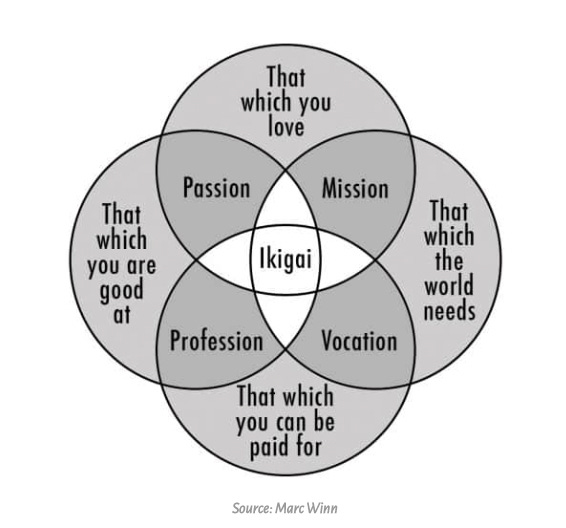

I was dissatisfied with the conventional Ikigai diagram promoted by Mark Winn in 2014:

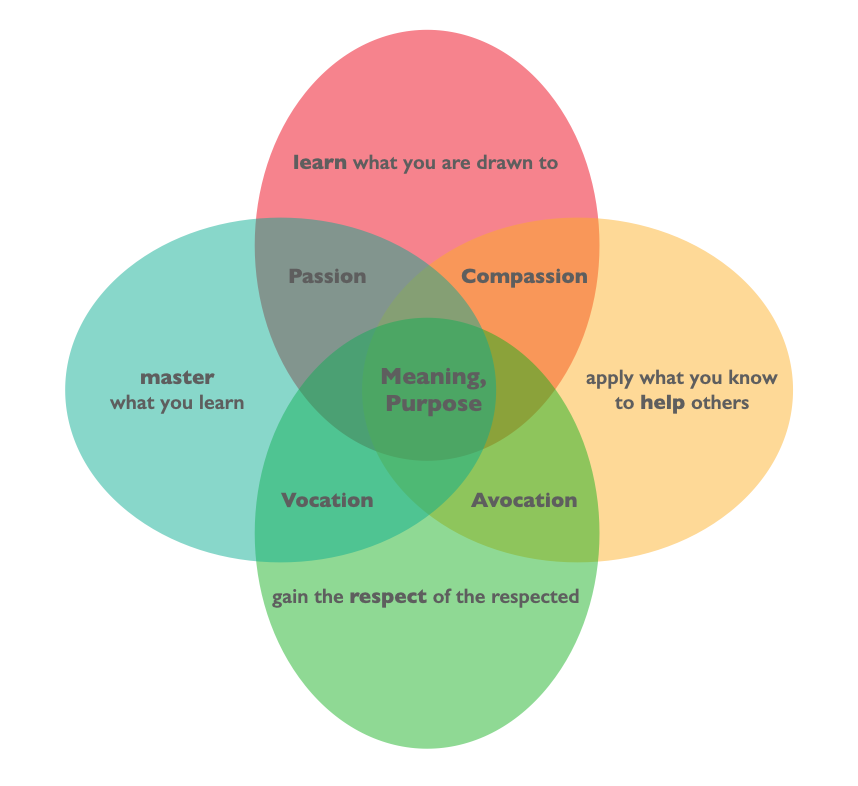

For me, I was intrigued by the underlying psycho-social model lying behind this apparently static chart. Consider this as a four-stage cycle: learn, master, respect, help:

Learn What You Are Drawn To — We should follow our natural curiosity to learn about the things in the world that interest us.

Master What You Learn — As we explore more of the aspects of the subjects of our curiosity, we approach mastery, which is the natural outgrowth of our pursuit of understanding and knowledge.

Gain The Respect Of The Respected — Our activities related to learning and mastery lead us to others who are likewise involved in their own efforts toward learning and mastery in the subject area we are investigating. We may come to respect those others, especially those who help us gain deeper understanding, such as those we work with. This leads naturally to wanting to gain the respect of the respected, as well.

Apply What You Know To Help Others — Helping others is a high calling. Choosing to help others in their own search for learning, mastery, and respect is the impulse of most teachers. And just as important is helping others outside of the learning relationship, in more direct ways, such as supporting family and community institutions, contributing time and money, or other forms of service.

The intersection points in this model are quite different from Winn’s Ikigai:

Passion — Our passion is where we are enmeshed in the loop of learning and mastery.

Compassion — Our compassion is the reflection of our involvement in community, and our efforts to apply what we know to improve the world, at any scale.

Vocation — Our vocation — our ‘calling’ — arises from our work toward mastery in the effort to gain the respect of those we respect. This can be plain old work — as in working for a living — but hopefully, it is more than just a paycheck.

Avocation — I use this more in the ancient Latin sense — a calling away from one’s work — and less in the modern sense of a hobby. For example, the doctor serving on her City Council is providing a service to her community independent of her medical skills. Note that she is likely to gain the respect of others outside the medical profession or her patients.

The heart of the cycle of cycles is meaning and purpose. As I wrote in 2023:

We can find meaning in any and all of the explicit circles and implicit loops of this diagram, which is an outgrowth of the dynamics involved.

Seasonality in Meaning and Purpose

The myriad points of intersection and inherent feedback loops in this Meaning/Purpose cycle of cycles each have their own ebb and flow. At different times, we push ahead on learning new skills, and, for a time, we apply older skills to new activities. I return to practicing Tai Chi after years away, or months pass where I am uninspired to write poetry, but instead become involved in a county initiative for traffic safety.

Our relationship to purpose may shift. I wrote, ‘Purpose is the reason we get up in the morning, the goals we set, and the sense of making progress toward those goals,’ and at times we may feel less connection to some, and more connected to others. A cold winter can cool more than our feet and hands, and, just so, a season of heat or rain.

Meaning is also a shifting ground beneath our feet. I sketched like this:

Meaning is a muscle, not a mood.

Meaning emerges from the myriad activities associated with the circles and loops of purpose.

It’s not a medal or a parchment with a seal of wax, but something that animates the space between us and others the way that a carpenter’s workroom smells of wood shavings, and how a crowded city square hums with ten thousand sounds of people walking, talking, and maneuvering their passage past each other and through, all happening at once, at once independent and dependent on each other.

In the diagram above, I placed Meaning and Purpose at the center, but I should have placed Meaning outside the diagram, as the field in which our striving, learning, actions and reactions cycle and reassemble.

We are too complex to be merely a stack of layers, we are each an assemblage of ten thousand cycles, each impacting the other, and so on, and so on. And each subject to the ebb and flow of the outside and the inside world. Paraphrasing Walt Whitman, ‘We are large, we contain multitudes’.

There is no summation of meaning: meaning must be considered as both tiny and enormous — independent and fully dependent — at the same time.

And subject to the phases of the moon, the length of the day, the wind in the trees, the migration of geese, the distant grumbling of trains across the night. We are both constant and inconstant, seeking and lost, finding and fumbling in connection to others.

Yes; it is a riddle, a prayer, and a fable, all at once.

Factoids

Plastics.

A recent United Nations study found that one out of every 20 objects moving through global supply chains is now some form of plastic — amounting to a trillion-dollar annual industry worth more than the global arms, timber and wheat trades combined.

A great example of markets being unequal to meeting the basic requirements of human life on Earth: markets are just for making money, with beggar-thy-neighbor economics and outcomes.

Anti-Curation, From The Archives

Anti-curation is a new service for paid subscribers: I’ll share less-than-wonderful articles that I have waded through for various topics, like Conscious Unbossing, so you can avoid them if you’d like.

Also, I share more behind the paywall materials from the archives of workfutures.io.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to workfutures.io to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.