What Comes Next

Charles Finch | The Big Freeze | You Need To Play More | Factoids: Fertility, Follow-ons To Plants Closing

In some sense capitalism is already behind us. We live here in its fevered midst, to be sure, but a recognition is emerging, especially among younger generations: It isn’t sustainable. The devastation of the natural world; the mindless consumerism; above all, the human misery that corporations trawl the world to extract, like ore, from souls as divine as yours or mine. All of it, increasingly, in service to the pathological greed of a few thousand mentally ill men. It cannot last. What comes next may be better, or it may be worse. But it won’t be this.

| Charles Finch, Her Job Was Real. So Why Did Her Work Feel So Fake?

…

Finch reviews Fake Work: How I Began to Suspect Capitalism Is a Joke, by Leigh Claire La Berge, and before saying a word about that book, he offers the quote above, which is grander in scope than La Berge’s ambitions.

He finds the work worthy of consideration and thinks Fake Work pursues a central truth:

The book is earnest, wooden, repetitive, but superbly committed to its own beliefs — truthful, dryly funny and often subtly moving. “To be a barnacle on the floating corpse of capital,” she writes. “Was that the most I could hope for from a professional life?”

“Fake Work” arrives at the right moment, too, with questions like that one in the air. Part of the spell cast by the runaway hit “Severance” was the ultimate literalization of the core truth La Berge is after: how completely corporate work estranges us from ourselves.

One of the goals of my ceaseless curation is surfacing ideas like Finch’s post-capitalism catechism and La Berge’s existential estrangement.

Note: La Berge is not rehashing Graeber’s bullshit jobs nonsense. This is an altogether different angle on work.

I’m seeking out antidotes against the poison pulsing in the bloodstream of work. Some have to do with changing how work is conducted, but first come the words, almost incantatory, serving as an attempt to frame and prefigure our future.

Send me your pointers, quotes, insights. Please. And subscribe if you can.

The Big Freeze

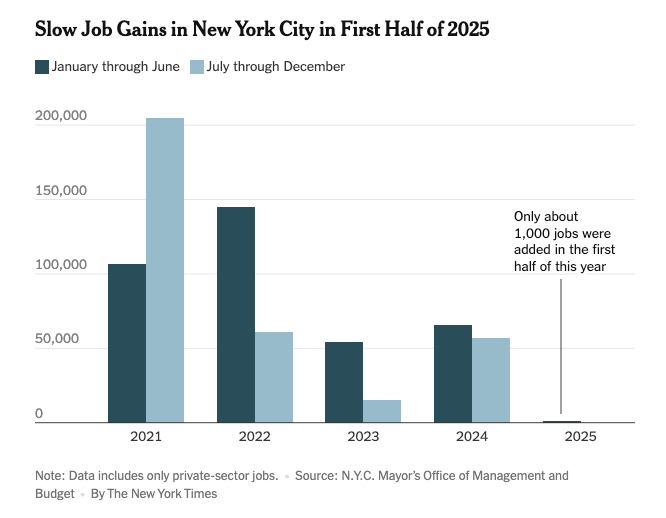

New York City, in its immensity, is often a harbinger of global trends. As an indicator of what many are calling The Big Freeze, fewer than 1000 private sector jobs were added in the first half of the year for NYC:

Haag’s analysis focuses on local NYC issues, what’s going on at restaurants and other small businesses:

The city’s unemployment rate of 4.7 percent is higher than both the state and the national average. The rate is much higher for some segments of the city’s population, especially young workers.

Business owners in the city said they first noticed a decline in business around March and have since also faced escalating costs on goods and materials, with vendors citing tariffs as the reason. As a result, they have curtailed hiring.

But then, he talked with Mark Zandi, the chief economist of Moody’s Analytics, who has a wider view [emphasis mine]:

Among New York City’s largest employment sectors, finance and insurance plays an outsize role in the city’s economy. The jobs pay an average of $387,000, more than three times the average annual wage of people who work in New York City. (The median household income of city residents is about $77,000.) Spending by financial industry employees underpins a disproportionate share of the city’s economy.

At the end of last year, firms had added nearly 30,000 finance and insurance jobs since just before the pandemic. But this year, they have lost 3,200 positions, and major companies like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley have announced large layoffs.

Mr. Zandi said that the emergence of artificial intelligence likely influenced the slowdown in finance jobs.

“There is a general view in financial services and professional services, both obviously very large in New York City, that A.I. holds enormous promise for doing things with less people,” he said. “That does affect hiring decisions.”

Perhaps most tellingly, the CEO of AT&T, John Stankey, sent a memo discussing results of an employee engagement survey, intended for his managers, that Dominick Reuter and Katherine Li revealed to the world.

Aki Ito nails her critique of the thinking behind this memo:

[It’s] perhaps the clearest attempt yet by a major CEO to rewrite the terms of the workplace in contemporary corporate America.

[…]

Now, here was Stankey — the CEO of a 140-year-old company that once epitomized corporate loyalty — declaring the death of loyalty himself. "Some of you may have started your tour with this company expecting an 'employment deal' rooted in loyalty," he wrote. "We have consciously shifted away from some of these elements."

That "employment deal" Stankey references is known by another name in organizational psychology: the psychological contract. As I wrote last year, it's the set of things that employers and employees believe they owe each other and are owed in return. Usually, these beliefs go unsaid — they're more inferred by the totality of a company's culture. What's unusual about Stankey's note is that he goes on at length making the implicit explicit, telling employees what they're right to expect from the company and what they aren't. Stankey says his workers deserve a transparent career path, a functional office, and the proper tools to do their jobs. But he says they're wrong to expect promotions based on tenure, the flexibility to work from home, and something about "conformance" that I can't decipher for the life of me. Most of all, he says, don't expect loyalty.

Yes, don’t expect loyalty. People are simply entries on the balance sheet, intended to convert their efforts into top-line results, and as soon as any person’s productivity falls below some designated line on a graph, out you go.

Denise Rousseau, the researcher who coined the term the psychological contract, sums up:

He isn't creating a new psychological contract — he's just ending the old one.

Stankey, and the other vocal CEOs involved in this defection from the old school, ‘we are a big team, working together’ days, are resorting to fear to keep people in line, and if workers don’t like it, fine: they are all betting on AI to thin the ranks pretty heavily in the coming years. So screw’em.

Meanwhile, the job market seems stuck (even leaving aside the new dog-eat-dog world that 21st Century CEOs gleefully are embracing). Rogé Karma has called this the Big Freeze:

Two seemingly incompatible things are happening in the job market at the same time. Even as the unemployment rate has hovered around 4 percent for more than three years, the pace of hiring has slowed to levels last seen shortly after the Great Recession, when the unemployment rate was nearly twice as high. The percentage of workers voluntarily quitting their jobs to find new ones, a signal of worker power and confidence, has fallen by a third from its peak in 2021 and 2022 to nearly its lowest level in a decade. The labor market is seemingly locked in place: Employees are staying put, and employers aren’t searching for new ones. And the dynamic appears to be affecting white-collar professions the most. “I don’t want to say this kind of thing has never happened,” Guy Berger, the director of economic research at the Burning Glass Institute, told me. “But I’ve certainly never seen anything like it in my career as an economist.” Call it the Big Freeze.

It sounds like a strange mirroring of the housing market, where people with low interest mortgages from before the pandemic don’t want to sell, so those seeking to get their first homes are blocked by low supply and high interest rates. In principle, the solution for the housing market is more housing, perhaps spurred by government incentives (which are certainly not seeing, at present). Except in the job market, young people (in particular) are trying to get jobs, and other (older people, in general) are holding onto their current jobs. And the employers hold all the cards.

What would it take for the Big Freeze to melt? A dramatic decrease in uncertainty (see ). Again, Karma:

According to economists and executives, the labor market won’t thaw until employers feel confident enough about the future to begin hiring at a more normal pace. Six months ago, businesses hoped that such a moment would arrive in early 2025, with inflation defeated and the election decided. Instead, the early weeks of Donald Trump’s presidency have featured the looming threat of tariffs and trade wars, higher-than-expected inflation, rising bond yields, and a chaotic assault on federal programs. Corporate America is less sure about the future than ever, and the economy is still frozen in place.

And, of course, a new Hobbesian philosophy among American CEOs, a culture of employment ‘red in tooth and claw’.

I’m reminded of the opening lines of Blood Simple by the Coen brothers, where private investigator Visser seems to be presaging John Stankey: