What the System Depends On

Charles Yu | The End of the System | Factoids

Working your way up the system doesn’t mean you beat the system. It strengthens it. It’s what the system depends on.

| Charles Yu, Interior Chinatown

…

The End of the System

I recently read a provocative Substack note by Nicole Eisdorfer that may superficially seem to argue against the Charles Yu quote above, but it doesn’t, really.

Eisdorfer maintains that the rise of quiet quitting — a term to refer to a specific form of disengagement — is a turning away from the system of scrambling to climb the slippery pole of personal advance at work [emphasis mine]:

Quiet quitting wasn’t laziness. It was the moment employees stopped giving away free labor to organizations that had already broken the deal. It revealed just how much discretionary effort the whole system was running on, effort given in good faith, because people believed in purpose, or in the promise that loyalty would pay off.

But loyalty didn’t pay. The longest-tenured employees were the first to be laid off, internal mobility dried up, and “above and beyond” got reclassified as “meets expectations.” Raises shrank to cost-of-living increases while shareholder calls bragged about profits.

Purpose, it turned out, was decoration. Profit was the real value.

The system depends, Yu tells us, on people trying to work up in the system. Eisdorfer is stating the inverse of Yu’s statement: if people don’t try to climb up in the system, the system fails. Or, if the system fails, one contributing factor is that people decided not to clamber up. And why do they drop out? Because the system is broken, and does not reward even those people who do what the system asks for.

The emergence of ‘quiet cracking’, she says, is the outcome:

Employees aren’t breaking because they’re weak. They’re breaking because the system has stripped out every buffer, every margin of safety, every ounce of trust.

If we were honest, we’d stop naming employee behavior like it’s the problem. We’d start naming the breaches of trust that caused it.

The system is broken, and getting worse.

I’m Stowe Boyd, and workfutures.io is my primary work. We are all inundated with a torrent of subscription requests: I'm no exception. I appreciate the attention, and I hope you’ll enjoy it enough to pay for a subscription.

Factoids

Employee engagement is a holding action.

All the efforts to increase employee engagement seem to be going nowhere:

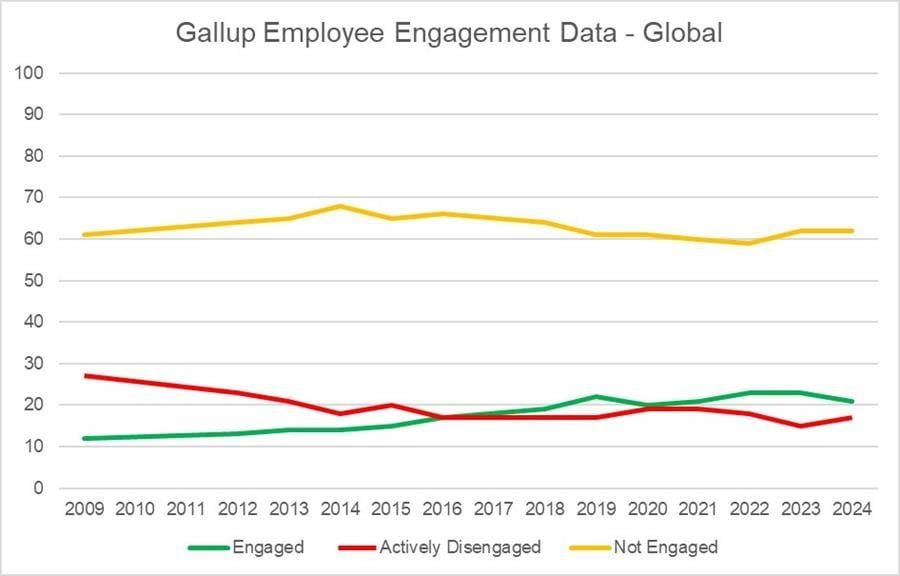

Several global spending estimates from 2024 agree on a figure around $1 billion just for the technological aspects of employee engagement. We should probably add at least a few million dollars to account for all the non-technology-related efforts to improve employee engagement — the workshops, training, focus groups, experiential programs, perks and incentives. That brings our global estimate for 2024 to nearly a billion and a half. In other words, global spending on employee engagement has doubled in the past 12 years.

In that same period — 2012 to 2024 — the percentage of employees who are not engaged at work decreased by just two percentage points (or about three percent), from 64% to 62%.

What’s more, the percentage of employees in the U.S. who are engaged at work recently hit its lowest point in over 10 years, and the percentage of employees not engaged in the U.S. was higher in 2024 than it had been since before COVID.

| Eryc Eyl, Employee Engagement Isn't a Lost Cause. We're Just Doing it Wrong

Eyl’s choice of title demonstrates his optimism, which is not reflected in the data.

I interpret this differently:

Whatever businesses are doing under the banner of employee engagement is — at best — a holding action, keeping the numbers from falling.

It’s unclear whether spending more would accomplish more.

It’s likely that whatever companies are doing is not actually tackling the right problems.

Very likely: there are systemic reasons people are disengaged at work — like the fundamental brokenness of our society — not just the charade that HR is performing for the quiet quitters.

…

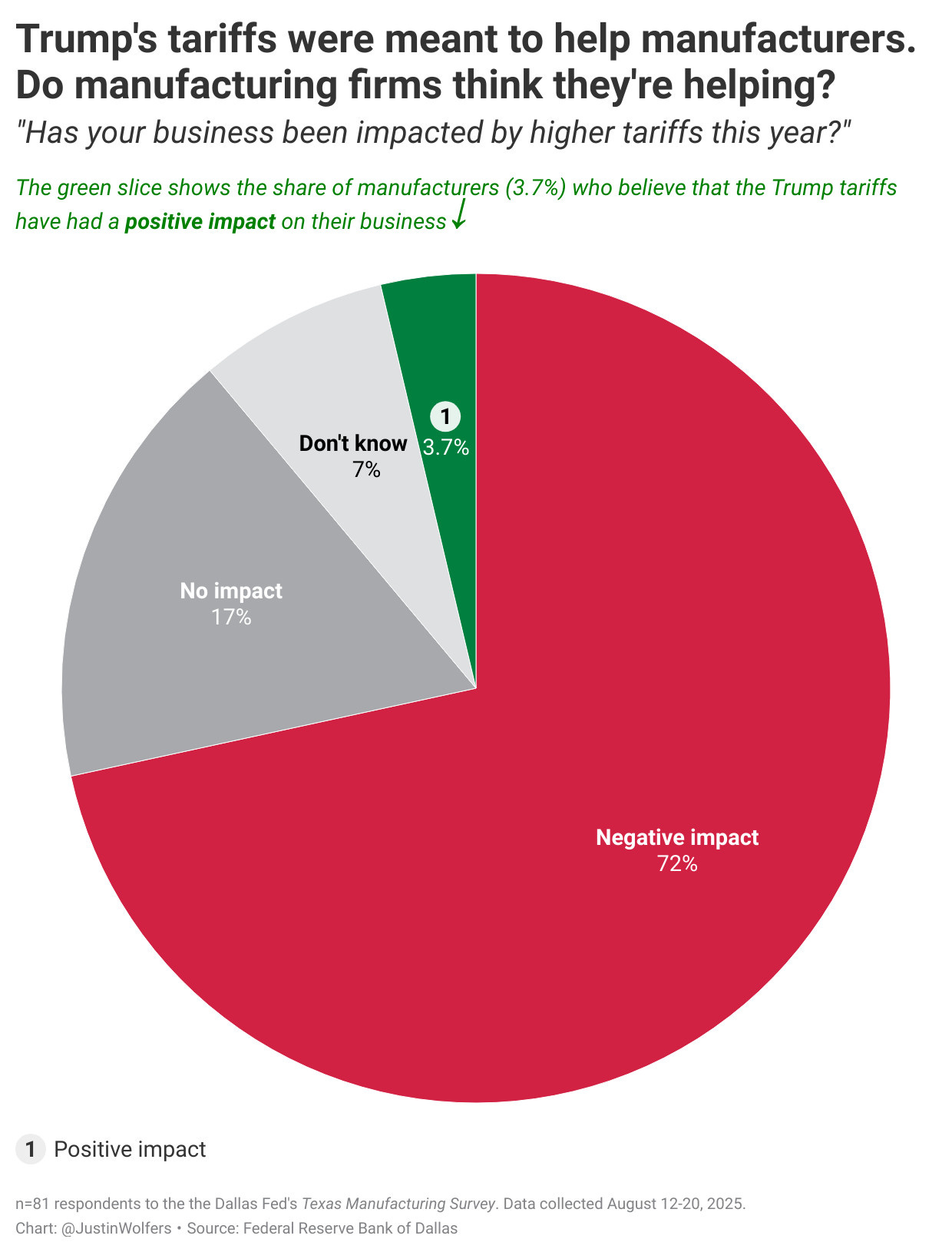

US manufacturers’ attitudes on tariffs.

Another reason to drop the tariffs: they are harming US manufacturing.

…

What’s in the balance?

The stagflation that is starting to show up in the US, due to Trump’s tariffs, endangers the world economy, not just the US.