Being Right Is Not a Strategy

Meredith Whittaker | Tim Wu Misses The Point of AI | MechaHitler | Publication Survey

Being right is not a strategy.

| Meredith Whittaker, What is AI? Part 1, with Meredith Whittaker

…

Whittaker ponders the question of democratizing AI. If we want to control AI’s potential impacts — and not leave it to the technoids and over lords to decide what to build and how to deploy it — just being right about the dangers is not enough.

I have lightly reviewed the EU’s AI Act, and that efforts seems like a giant step in the right direction. More to follow.

Tim Wu Misses The Point of AI

Tim Wu, responds robotically to recent claims by Dario Amodei of Anthropic and other tech overlords about the devastation — a ‘white-collar bloodbath’ — that AI will bring to the economy, our culture, and our lives.

I’ll start with am eminently quotable, but ambiguous, line from Wu’s closing statements:

The wholesale replacement of human work makes for good science fiction but a bad future.

What does he mean by ‘a bad future’? A bad prediction about the future? Or a future that would be bad for those living in it?

I’ll return to that in my own close, but (hint, hint) I think he’s not focused on the second alternative, but I am.

Subscribe to have this newsletter delivered to your inbox. Get a paid subscription to gain access to almost 1000 posts, reaching back to 2013, and my deep appreciation.

First off, Wu crudely breaks the world into two camps. Hi ‘pessimists’ (not explicitly named as such), like Amodei and Zuckerberg, who are in my mind the far fringe, advocating for firing as many people as possible, basically to put more money in the pockets of owners and execs.

(The counter to that is ‘who will buy the goods and services if everyone is automated out of work?’. But leave a sustainable world system to one side, for now.)

On the other hand, Wu offers up ‘optimists’:

Optimists push back with a different prediction, forecasting that A.I. won’t replace white-collar workers but will rather serve as a tool that makes them more productive. Jensen Huang, the chief executive of the computer chip maker Nvidia, has argued that “you’re not going to lose your job to an A.I., but you’re going to lose your job to someone who uses A.I.

Wu’s ‘optimism’ means only three jobs out five will be eliminated, perhaps. The only difference between optimism and pessimism to Wu is how many chairs are left at the end of musical chairs.

Both sides in this debate are making the same mistake: They treat the question as one of fate rather than choice. Instead of asking which future is coming, we should be asking which future we want: one in which humans are replaced or only augmented?

This reminds me of Rebecca Solnit’s thoughts on optimists, pessimists, and the hopeful:

Hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act. When you recognise uncertainty, you recognise that you may be able to influence the outcomes – you alone or you in concert with a few dozen or several million others. Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable, an alternative to the certainty of both optimists and pessimists.

Wu forgets the third third: the hopeful uncertain. He has only considered those that are certain: optimists and pessimists, secure in their certainties.

He also seems to imply a third way of approaching AIification of work, but he is basically adopting the ‘optimist’ stance. His ‘augmentation’ is treated as the only alternative to the obliteration of work. What about actively regulating the rate that AI is introduced into the workplace?

Wu mouths the productivity argument for AI:

More important [than the creators of AI tools] are the employers who adopt A.I. systems: If they really want productivity gains, they too must embrace A.I. programs that augment rather than replace.

Huh? If creators do make AI that replaces humans, that would be a productivity gain, right? He seems to be discussing a trade-off between naked productivity by cutting workers and a greater sort of increased results from augmentation.

But unsaid might be the argument that decisions made by AI overlords or corporate chiefs shouldn’t lead to a bloodbath.

Do people have a right to work, to gainful employment, and the right to live in a society where social policies are not solely determined by tech firms and large corporations?

The step-by-step breakdown of established industry work patterns by the introduction of new technologies is well-documented. Consider the example of the chainsaw, and what its introduction did to logging. The highly-trained, ax-wielding loggers of the pre-chainsaw era had amassed difficult skills — did you know the two edges of loggers’ axes had different angles, one for angled and the other for lateral cutting? — and the chainsaw allowed dramatically lower-skilled workers to enter the logging workforce, driving down the pay for existing loggers. This commodification of that work was never countered by later technological or economic changes: all loggers are paid significantly less than the old-timers were, and there were fewer of them, too.

What will we do — as a world society — if 90% of all skilled jobs’ pay scales are devalued by even 25% due to ‘AI augmentation’?

And don’t say that the old-school loggers moved to other industries, got reskilled, and reached high pay again: they didn’t, mostly. The same is true of skilled weavers in the Luddite era, autoworkers laid off by automation and off-shoring (see Remember Lordstown), and myriad other instances of displacement.

But Wu offers up examples of technologies curtailing various sorts of labor — in his terms, ‘augmentation’ — that we have grown accustomed to:

Augmentation is not any kind of panacea: In yielding greater efficiencies, it will lead to job loss. But that was also true of augmenting technologies like the tractor and the personal computer, innovations that were worth their disruptive trade-offs.

Wu never discusses the comparative time frames of these disruptive technologies. PCs took decades to become commonplace. Culture adopts technologies more smoothly when there is sufficient time for individuals to transition. Wu never discusses these changes from the perspective of the individual, except implicitly, like the hypothetical programmer deciding to adopt co-pilot.

There’s a world of difference between productivity gains and a systematic plan of industry-eliminating unemployment. Indeed, as the economist David Autor argues, A.I., done right, could help rebuild the middle class by giving a broader range of workers access to expertise such as software coding that is currently concentrated among higher-skilled workers. It all depends on how the technology is implemented.

Again, the case of the relatively unskilled logger who adopts the chainsaw as a personal productivity gain, but all skilled loggers find their skilled work commodified. Will all skilled coders find their livelihoods marginalized by a crop of Microsoft-Copilot-assisted programmer apprentices? If the scarcity of coding talent is ‘solved’ by tools that allow the unskilled to take the place of gurus, fairly quickly there will be fewer programmers and lots of hours of compute burned by Microsoft servers.

The most glaring omission is that Wu never suggests that we curtail -- or drastically slow -- the dispersal of AI. What will we do — as a world society — if 90% of all skilled jobs’ pay scales are devalued by even 25% due to ‘AI augmentation’? When you consider the social impact of commodifying the inner workings of law, medicine, finance, logistics, education, and so on, the rate of change is very relevant. If managed over, say, a hundred years, we might be able to avoid a catastrophic collapse of the economy; but if unbridled tech lords and corporate decision-makers decide to push as past as technologically feasible, the scenarios become pretty grim.

When Wu says ‘it all depends on how the technology is implemented’, he’s not wrong, but he leaves out ‘how fast’.

He does touch on time frames in an oblique way in his closing paragraph:

Augmenting humanity has been the aim of technological development since at least the Bronze Age, and that should continue to be our goal even as we develop technologies that mimic human intelligence. The wholesale replacement of human work makes for good science fiction but a bad future.

I think the timeline of technological development is better considered in phases. One can make the argument that the ‘aim’ of technology in the Bronze and Iron Ages was the consolidation of power and the rise of militarized empires, and we might stretch ‘augmentation’ to mean augmenting the would-be rulers of would-be empires over everyone else.

The aim of technology in the Industrial Age was the transition from human labor — in agriculture, manufacturing, and transportation — with massive disruptions as formerly manual work was displaced by machines: like the chainsaw and the loggers, the mechanical loom and the Luddites, and horse-drawn carts replaced by railroads, trucks, and airplanes.

The aim of technology in the Information Age, however, has always been — and continues to be — to emulate human capabilities of computation, communication, and coordination. But a hastening rate of change is potentially destabilizing.

It took only 66 years from the first powered flight to humans landing on the Moon, compared to the millennia between the Iron and the Industrial Ages.

Wu lands wrong-footed with his throw-away line, ‘The wholesale replacement of human work makes for good science fiction but a bad future’.

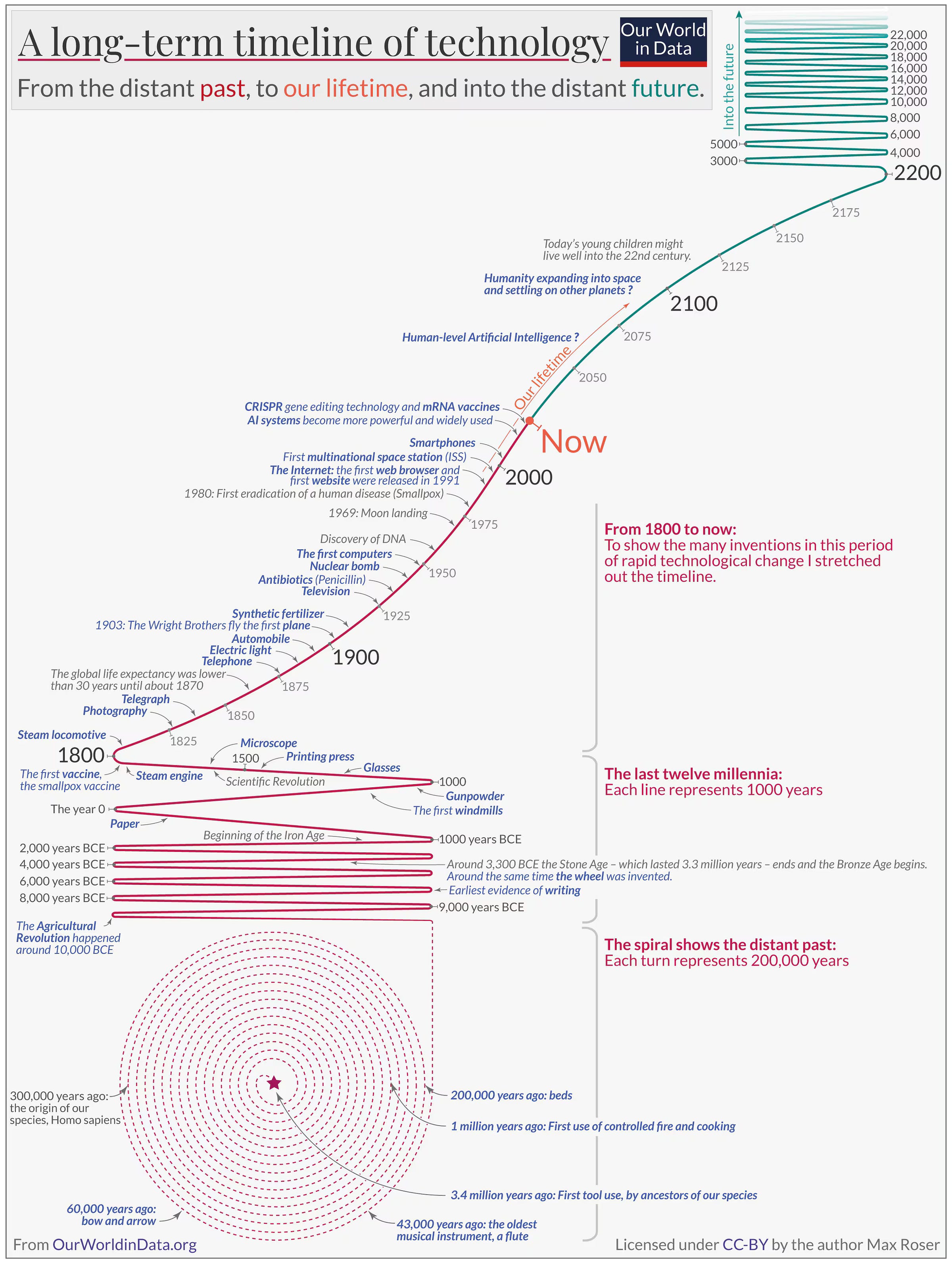

If you examine Roser’s timeline in the chart above, you see a cascade of technologies that undermine established sorts of work, but a lot are left out. Where are spreadsheets and work processing, eliminating work for millions of bookkeepers and secretaries? The chain saw? The tractor? The telephone switch, leading to the near extinction of telephone operators?

Those breakthroughs are not as splashy as walking on the Moon, splitting the atom, or editing genes, but they clearly led to cadres of skilled workers being pushed out of their lines of work. That is not science fiction: it’s historical fact. And there are a lot of indicators that AI could be like a neutron bomb, striking all of us indiscriminately, without regard to how skilled we might be.

MechaHitler

And that doesn’t even touch on Grok and MechaHitler.

Becoming a Multi-Contributor Publication

I have been considering the question: should workfutures.io transition to being a multi-contributor publication. There are many reasons to consider that course:

Other Substacks — like Work3 — are adopting this approach, because they are reading the same tea leaves as me.

There is continued growth in Substack pubs, who are contending for the subscription dollars of a slower-growing reading population.

More readers are expressing ‘subscription fatigue’: too many subs, too many alternatives.

What to do?

I am beginning to approach other writers, thinkers, and analysts who publish independent Substack newsletters, to assess their thoughts on turning workfutures.io in a collective activity. This could mean higher payouts for all involved, given the following premises:

A publication with, say, 10 contributors each writing once or twice a week, would be able to attract considerably more readers1. This would start by the combination of the readers from the individual newsletters, and would continue by attracting new readers at a faster pace.

Even if the ten-contributor publication could not charge ten times as much as today’s newsletter does, with a greater base of readers, increasing subscription to a low multiple of todays’ $5/mo could potentially lead to more revenue.

I would like to get your participation in a survey to gather the workfutures.io ‘community’ to weigh in on these questions, to assess the interest and ideas of the group. Click on the image below or this link to fill out the survey. Thanks for your time.

Given consistent high quality, of course.

You seem to overlook the idea that most people don't expect to have a job for life anymore.

Most likely, the main reason for loggers not reskilling at the time was that they expected to be loggers for life and the economy was not set up for reskilling.

Things are very different now, which means I find the argument for slower introduction of AI not carry strong.

Adaptation is *much* easier now than it was in the past.

It was UK government policy after WW2 to run the economy to achieve full employment and pursued by both main parties. Reagan and Thatcher came along and ripped up that consensus, handing our fate over to ‘the markets’, which really means ‘the rich’.

We don’t have to passively accept whatever the Tech bros and Corporations decide to foist upon us. We have agency and can demand alternatives, for a different set of priorities. I can only see the current paths, pessimist and optimist. leading to unrest and violence.