Minimum Viable Meetings

'How and why should we meet? And who decides?' asks Priya Parker

I’ve been taking some time ‘off’ — meaning spending time doing other things than Work Futures. I have new opportunities for work, which is reinvigorating me, and at the same time, I have decided to drop other drudgery that I have been doing for years, most specifically writing reports about technologies I don’t personally use.

…

I was happy to see that Substack has acquihired the team behind Cocoon, an app for small group communication. That team will be working on fostering a greater sense of community between Substack authors and their followers. I can’t wait for that.

Quote of the Moment

While jobs are sustenance, careers are altars upon which all else is sacrificed.

| Cassady Rosenblum, Work is a False Idol

I really admire Priya Parker. She’s a force of nature, and has shed a great deal of light on how to make face-to-face gatherings more meaningful. And she recently raised some great questions wondering about the decision-making behind back-into-the-office power dynamics in The Pandemic Showed Us How to Have Better Meetings.

She asks:

How and why should we meet? And who decides?

But she quickly settles into some workwashing before providing really good recommendations:

After the pandemic hit, we began to sense what we can do even better virtually (the use of chats, breakout rooms and polling), as well as the limitations of not being in the same physical space (lively unmuted brainstorming, complicated coordination, spontaneity).

My quibble is this: brainstorming in groups has been shown to be less creative than individuals ideating independently. And the folklore about spontaneity in the office -- chance encounters, great ideas arising at the water cooler or coffee machine -- has become the Big Lie in the rationalizing about BITO.

Asking employees if they want to “return to the office” is asking the wrong question.

| Priya Parker

But she goes on to make really good points, in essence making the argument for emergent decision-making (and an implied emergent organization behind it all) about where and how to work:

Asking employees if they want to “return to the office” is asking the wrong question. Instead, managers should ask: What did you long for when we couldn’t physically meet? What did you not miss and are ready to discard? What forms of meeting did you invent during the pandemic out of necessity that, surprisingly, worked? What might we experiment with now?

This experimentation should be a dialogue among management and staff, not an edict handed down. It opens radical possibilities. Perhaps you let employees continue remotely but bring them together a few times a year, focusing those gatherings on forging connections strong enough to sustain far-flung teams. Perhaps, like Dropbox, you go “virtual first” and allow employees to book local studios when they determine in-person collaboration is warranted.

I completely agree that there should be a dialogue about the workplace, namely the status quo ante shared office, and the workscape, which is the multiple physical and virtual spaces that we share to get work done and which includes the workplace as one modality. In an emergent organization, each person can independently choose how, where, and when to work, and the organization will take steps to support the individual as well as bridge the interdependencies of group work.

Parker cites When Do We Actually Need to Meet in Person? by Rae Ringel, who gets to the right questions, but can't help bowing to the graven idol of serendipity along the way:

Now that serendipitous in-person interactions are possible, and now that we know how to do virtual work well, let’s think very carefully about whether time spent meeting might be better spent thinking, writing, or engaging in other projects.

This was published in July 2021, and so it was written in the false dawn before Delta arrived to screw up the back-into-the-office push. But the conclusion -- let’s think very carefully about whether time spent meeting might be better spent thinking, writing, or engaging in other projects -- stands better alone, without the head fake toward serendipity.

She continues in a productive vein, answering her first question is 'should this be a meeting?':

Less is more: The fewer meetings we have, the more the ones we have will count. It all comes down to purpose. Ask yourself: Why are you meeting? Make sure the answer really makes sense. Do you really need to meet? Prioritize asynchronous work and use meetings to be creative and do something together, rather than simply share information.

She makes a short case for asynchronous coordination -- members of a team individually posting project status, for example, instead of the typical boring, round-robin -- but then reverts to the trope of glorious brainstorming, the only true wellspring of human creativity, it seems:

Meetings for team members to provide progress reports, for example, where every individual has their segment but is relatively passive the rest of the time, may not be necessary. Here, the goals may be accomplished more efficiently in writing. On the other hand, brainstorming sessions, where people are building off of one another’s ideas, benefit from the dynamics of a gathering.

As is so common in these articles, there is no research cited to support her claim about brainstorming. And as someone in the business of facilitating meetings for large companies, her inclination toward facilitated brainstorming meetings is unsurprising, perhaps.

I would be even more aggressive in questioning the rationale for any given meeting and start with the premise that it shouldn't be scheduled. What specific criteria lead to the conclusion that the interactions between a group of people should be channeled into a face to face, IRL meeting?

It's been my experience in business that these models of decision-making are not made explicit, and companies flounder in a twilight half-world of uncertainty, where the participants in decision processes have not established basic principles.

One general approach is to use non-meeting decision-making approaches first, and only convene a meeting after those approaches do not succeed in some tangible way.

For example, consider a hiring decision. A group of people have interviewed a candidate, and they have shared their views asynchronously without coming to a consensus. Rather than calling a meeting, can we step back and ask some context-setting questions? Is it the company's policy that all hires require a full consensus of the interviewers? Or is the policy an advise-and-consent model, where someone -- perhaps the manager or team leader who will be working most closely with the candidate -- has the responsibility for the decision, so long as all interviewers consent, and where all invalidating dissent has to be backed by a reasoned consideration, and not just some gut intuition?

It's been my experience in business that these models of decision-making are not made explicit, and companies flounder in a twilight half-world of uncertainty, where the participants in decision processes have not established basic principles. It may seem a good use of time to plan for a meeting to review a possible hiring decision, but it may just be a shortfall in other approaches, for example, the team lead could have a one-on-one exchange with someone raising concern about the candidate's work history, for example. That doesn't necessarily require the dedicated attention of all the interviewers who do not share that concern.

I offer the minimum viable meetings model, which is meetings should not be proposed until non-meeting approaches are tried, and fail to lead to closure.

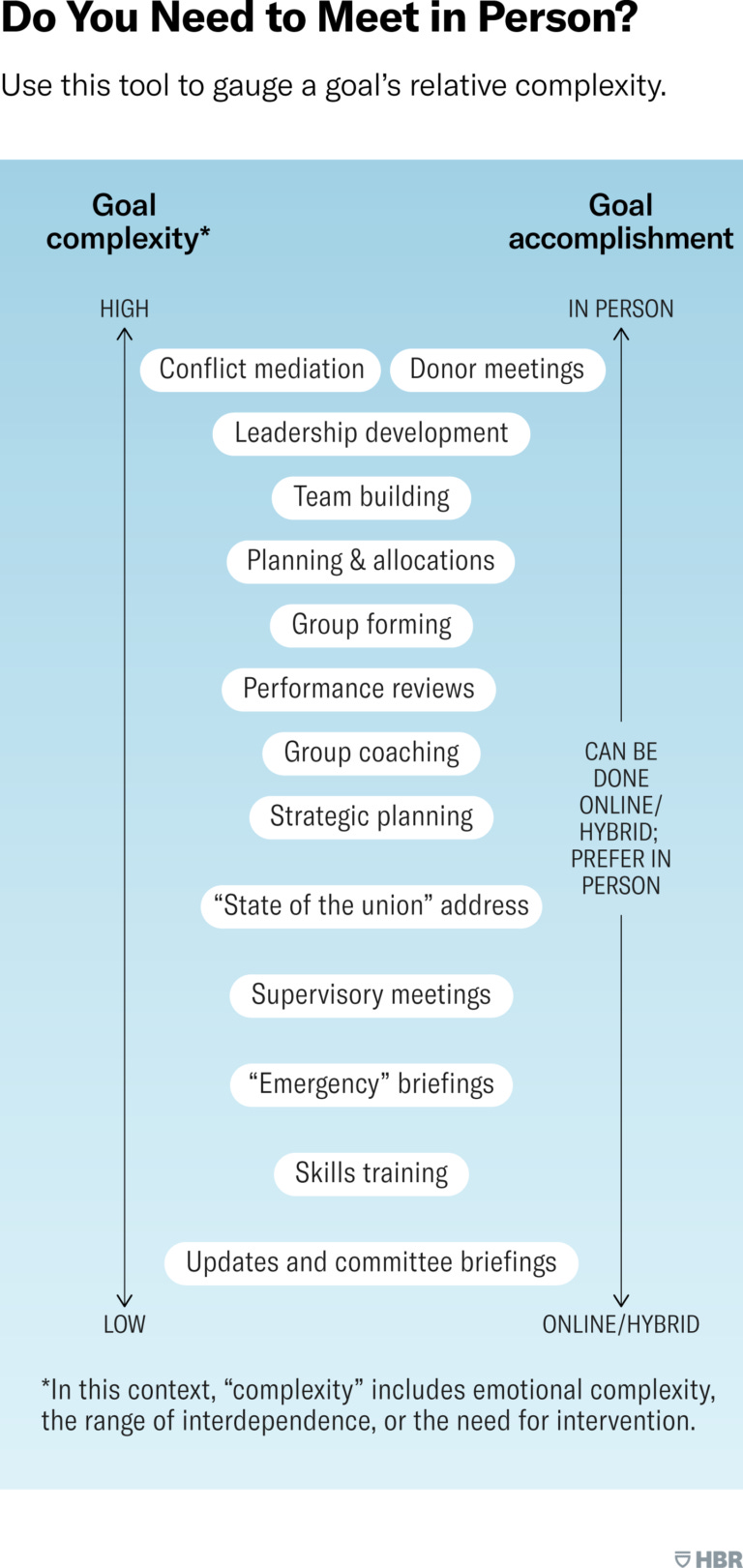

Ringel says she uses a chart like this to decide between face-to-face/synchronous and remote/asynchronous modes of coordination, and all shades in between:

I think this chart represents the sort of nebulous thinking that leads to creating nebulous meetings, as opposed to a sieve that winnows out the few meetings that must be face to face.

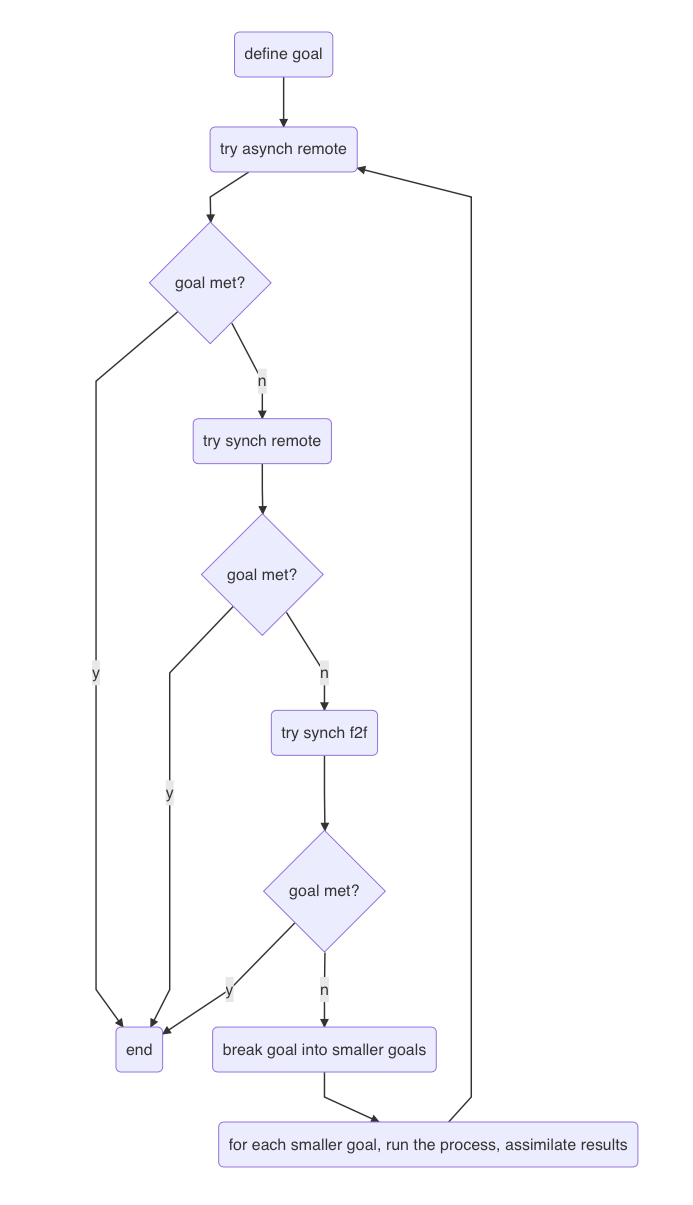

Personally, I'd rather start with the baseline of no meetings, and use an approach as flowcharted below, instead of trying to apply a case-by-case analog 'tool' like the chart above.

In the flowchart below, the participants in some work process start with asynchronous remote communications and escalate to synchronous and face-to-face approaches only when the goal is not met. If even a face-to-face meeting doesn't resolve the issue, break the goal into a set of smaller goals, and try again.

I haven’t made the case for cost savings by avoiding mass meetings, but I should. I forget who said it, but companies allow anyone to call a meeting costing thousands but require approval to buy a $50 book.

One final observation: Delta may slow the day of reckoning for executives who want call workers back into the office, but they want to. They really want to.

From Robert Half’s August 2021 report:

In a survey of more than 2,800 senior managers in the U.S., 71% of respondents said they will require their teams to be on-site full time once COVID-19-related restrictions completely lift. Far fewer will allow employees to follow a hybrid schedule, where they can divide time between the office and another location (16%) or give staff the complete freedom to choose where they work (12%).

Meanwhile, the resistance is growing: a Bloomberg survey from May 2021 reveals that 39% said they’d consider quitting if their employer wasn’t flexible.

In a follow-up to this post, I will look into what is motivating so many to consider quitting.

Thinking on Ringel's chart… I think that a workplace philosopher, you are more interested in the principles that forge such a rubric. I think that your flowchart is closer to a set of base principles or thinking process that (within the context of a team) could lead to a rubric.