You’re Already Behind

Umberto Eco | The Making Of Lists | Factoids

We make lists because we don’t want to die.

| Umberto Eco

…

I actually took the title of this issue from Anne Lamott, a few paragraphs into the first section:

By the time you get around to everything on any one list, you’re already behind on another.

The Making Of Lists

Lists — whether jotted on paper, managed in an app, or even held only in memory — are a form of complaining.

This is most clear when one person creates the list to tell another what they should be doing, or should have been doing, instead of screwing around doing other things not on the list at all.

But I maintain that even when we are creating lists for ourselves, we are complaining. It’s an indirect sort of complaint, a list. Still, it serves as an inherent judgment of our inability to get everything done, prioritize adequately, juggle time successfully, and focus on the next best thing to do out of all the possible things to do.

A list is accusatory in that way.

The wonderful Anne Lamott is not quite as existential as Umberto Eco (in the quote above), but in Bird by Bird, she touches lightly on the inescapable incompleteness and immensity of lists:

We have so much to remember these days. So we make all these lists, filled with hope that they will remind us of all the important things to do and buy and mail, all the important calls we need to make, all the ideas we have for short stories or articles. And yet by the time you get around to everything on any one list, you’re already behind on another.

But, in a quintessential close, she expresses belief in lists:

Still, I believe in lists and I believe in taking notes, and I believe in index cards for doing both.

I will leave to one side Lamott’s affection for index cards1, and focus on her observation, ‘by the time you get around to everything on any one list, you’re already behind on another’. And not only behind on another, but lost in the expansiveness of lists, since there can be as many lists as there are thoughts in our heads, or possible disasters we worry ourselves with.

I am reminded of a distinction that may play here. E.M Schumacher — in Small is Beautiful — cited the vast difference between convergent and divergent problems:

G.N.M. Tyrell has put forward the terms “divergent” and “convergent” to distinguish problems which cannot be solved by logical reasoning from those that can. Life is being kept going by divergent problems which have to be “lived” and are solved only in death. Convergent problems on the other hand are man’s most useful invention; they do not, as such, exist in reality, but are created by a process of abstraction. When they have been solved, the solution can be written down and passed on to others, who can apply it without needing to reproduce the mental effort necessary to find it. If this were the case with human relations - in family life, economics, politics, education, and so forth - well, I am at a loss how to finish the sentence. There would be no more human relations but only mechanical reactions; life would be a living death. Divergent problems, as it were, force a man to strain himself to a level above himself; they demand, and thus provide the supply of, forces from a higher level, thus bringing love, beauty, goodness, and truth into our lives. It is only with the help of these higher forces that the opposites can be reconciled in the living situation.

A digression into divergence and convergence.

I believe there are two classes of lists, divergent and convergent. Convergent lists can be ‘solved’. A shopping list, for example, involves finding the various items on the list at a store, paying for them, and bringing them home. Easy.

Divergent lists, however, are quite different. Consider a list intended to outline the research process for an essay on a complex subject, such as the impact of climate change on wildfires. A rudimentary list — 1. research the topic, 2. analyze and synthesize findings, 3. write the report — may seem to capture the sequence of the research, but fails on closer examination. Why? Because zooming into the specifics of climate change and wildfires reveals expanding complexity at whatever granularity of focus.

Divergent problems do not have a defined stopping point. You can’t reliably just break them into smaller bits that are more tractable than the entire problem. The bits are themselves just as complex as the whole: they are wholes, too. As Baldur Bjarnason observed,

A problem like this becomes more complex and hard to solve under close analysis, not simpler and easier to solve. The more detail you see, the more conflicting data points you encounter, and the harder it gets to reconcile the diversity you’re witnessing with a cohesive mental model.

This is an abyss we are all confronted with. Our recourse is to take mental shortcuts, basically sealing off the complexity of a list element like ‘2. analyze and synthesize the findings’ by pretending it is convergent instead of divergent. And then, later, when undertaking the work associated with that step in the project, we lie to ourselves and the world by simplifying complexity through the application of models. That’s where the magic happens.

And if we didn’t, we’d be unable to use lists effectively. And we do. So I believe — like Lamott — in lists.

One model to reduce divergence: limit tasks.

I was motivated to write The Making Of Lists by Andrea Leigh Rogers, who reached the end of her rope with her ‘endless to-do list’ following a move when she was simultaneously

restructuring my business, managing school logistics, and navigating a divorce all at once. I had big plans and even bigger responsibilities, and even though I knew I was doing my best, I was overwhelmed and out of sync. Despite constant effort, I didn’t feel like I was making real progress; I was doing everything but not really achieving anything. I needed to reclaim clarity, and fast.

She settled on a daily regime with six tasks, only:

I started with a blank sheet of paper and wrote down just three things: the highest-priority, biggest-impact actions for that day. These were my nonnegotiables. At the time, they were things like finalize a franchise agreement, review legal documents, renew a passport.

Just three high priority tasks I told myself I would absolutely get done, no matter what.

Once those were completed, I didn’t move on right away. I took a beat and recognized the win. I even gave myself a quiet, mental “Atta girl.” Because progress deserves acknowledgment.

Then, I added two bonus tasks, things that would also move my day along but wouldn’t be the end of the world if I didn’t get to them. Finally, I added one “feel good” action: something to look forward to that restored energy. That might’ve been a 15-minute walk, calling a friend, or trying out some new skincare. Just a tiny, intentional reset.

What I created was a reverse pyramid:

• 3 must-do items

• 2 nice-to-haves

• 1 mood-boosting reset

It was short, focused, and completely doable. And it changed everything.

That day, I got more done, not by doing everything, but just by doing what really mattered. My decision fatigue lifted, my energy returned, and I had a clear view of what success looked like. I finally had momentum, and it felt good.

She avoided the many snares of multiple lists, and dialed down her focus to what could be accomplished during a single day.

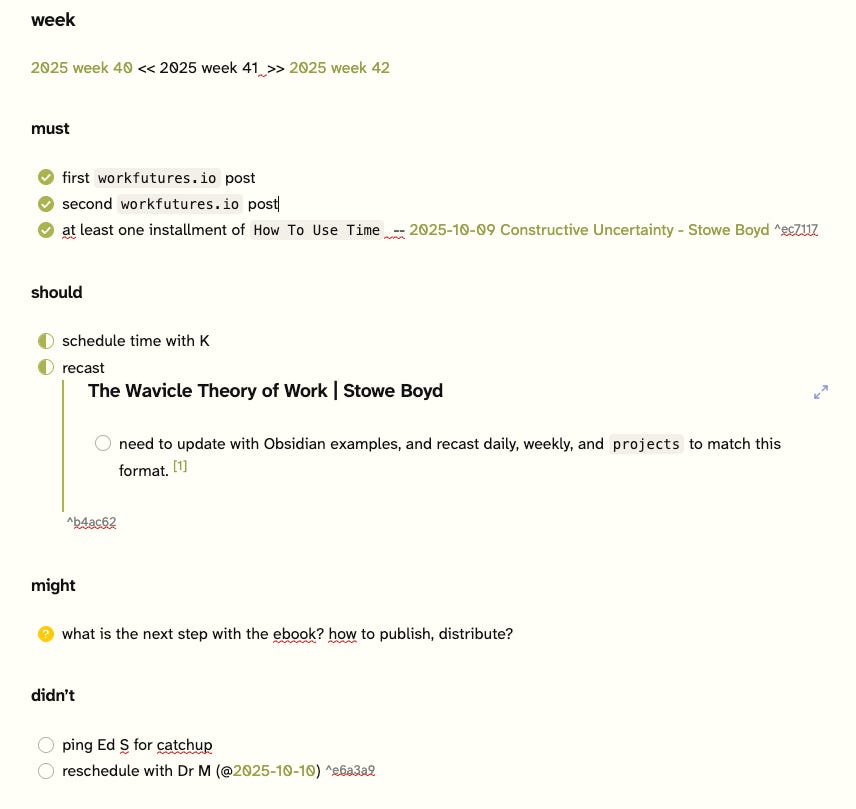

I used a similar daily technique for years that I called the 1, 2, 3 technique: 1 large (complex) task, 2 medium tasks, and 3 short tasks. As I have aged (wisdom), I found the daily focus a bit constraining. So my approach has evolved into a weekly list, updated on Mondays, with a small number of tasks — less than twenty — placed in four categories: must, should, might, didn’t. Here’s a recent example, somewhat edited for public consumption:

I’ll leave aside the nuts-and-bolts of how I manage this (in Obsidian), but the basic idea is clear: I start the week’s list on Monday, often pulling the unfinished from the previous week’s list. Some of the entries are convergent: like pinging my old friend Ed to set up a time to catch up (although I didn’t get to that during the week, so I moved it to didn’t). Both of the shoulds on this list are marked ‘in process’ (using the half-and-half icon). The single might is just a conjecture to perhaps investigate (I didn’t, but I will someday). The musts are where I focus the greatest attention, and, of course, if I fall short, I move the items to didn’t, although I work diligently to accomplish my musts.

My common practice when creating the new week’s list is to link back to incomplete items in last week’s list and link them into the appropriate sections for this week. Or maybe not. I let things fall off my lists if I’ve changed my mind, or if new tasks come to fill the foreground. I’m a scruffy.

More of a menu than commandments.

My final observation is about the underlying psychology of making lists. To cut myself some slack — and avoid the sense of judgment latent in lists — I now treat my to-do lists more like menus and less like commandments carved in stone. I try to give myself room to pick and choose, making hard time commitments only when other people are involved. For example, I’ve committed to my readers here at workfutures.io that I’ll post at least two issues of the newsletter (and at least one issue of the ‘How To Use Time’ series) every week.